“The black fly, or simuliid, is the least known and understood major trout food in North America. With a staggering wealth of scientific observation plainly accessible to angling researchers, how could the simuliids have been overlooked by experts and recreational anglers for so long?” Jeff Morgan, “Productive Trout Flies for Unorthodox Prey” (Frank Amato Publications, 2012)

The Western Cape province of South Africa has its rain in winter and by 15 October the water level has normally dropped sufficiently for fishing to be feasible and this is the most productive time of the year for fly fishers.

The streams near Cape Town do not have significant hatches of mayfly or caddis, but early spring has two major, albeit very brief, hatches.

Two insects, the Net-Winged Midge (Blephariceridae) and the Black fly (Simuliidae) hatch in substantial numbers. On one occasion on the Elandspad stream, the Mountain Midges – as they are also known – were so prolific that they looked like small, drifting patches of grey mist.

http://www.troutnut.com/hatch/884/True-Fly-Simuliidae-Black-Flies

Click in images to enlarge

The Molenaars River 40 minutes from Cape Town and typical of a Cape stream

I have seen black flies in their hundreds on the rocks in early Spring, mating, then laying their eggs in little pink patches which quickly turn brown and resemble lichen. Many end up in the water and this can cause a frenzy of selective feeding.

A female black fly laying eggs on a Cape stream. The eggs turn brown as a camouflage mechanism and within a few days hatch and move below the water surface.

They are also prolific in the rivers of the Eastern Cape Highlands.

Black fly larvae in the Kraai River in Barkly East – Photograph by Fred Steynberg

I think we underestimate the role that they play. The only reference that I have ever found to imitations of black fly larvae being fished locally is a pattern developed by Keith Wallington for yellowfish on the Vaal River

In his book, Productive Trout Flies for Unorthodox Prey, (Frank Amato, 2012) Jeff Morgan writes: “I located more than 20 studies where black flies were, at least for a month or two, by far the most important food resource for trout, not to mention dozens more where black flies ‘only’ were more important than every single mayfly species with the exception of Baetis!”

“Female black flies can swarm and concentrate egg laying in a relatively small section of stream. One study found a 10 metre section of a small stream with 3 million eggs, the result of 3750 females laying eggs synchronously!”

Morgan says that on many US trout streams black fly make up the predominant food source in June and July – the height of the American summer.

http://www.west-fly-fishing.com/feature-article/0204/feature_657.php

Trout in Africa are no different. Vernon van Someron spent two and a half years studying trout for his 1950 PhD thesis, ‘The Biology of Trout in Kenya Colony’.

He was based at the Kenyan Government’s River Research and Development Centre situated on the Upper Sangana River, but his study also encompassed 15 other rivers and streams in the country which held trout.

His finding, based on stomach content analysis, is unequivocal:

‘Simulium larvae are eaten in the greatest percentage, form the greatest bulk of the aquatic food taken, and are found in the greatest percentage of stomachs. Together with Simulium, Baetis nymphs constitute a major portion of the aquatic food eaten.’

Van Someron’s findings in Kenya are replicated in a photograph of the stomach contents of trout caught on the Bell River in Rhodes by local guide Fred Steynberg. When he stomach pumped the trout it was found to contain only two prey species, Baetis nymphs and Simulium larvae – 17 of the former and nine of the latter.

This trout, caught by Fred Steynberg in Rhodes shows the predominance of Baetis nymphs and black fly larvae in trout diet.

http://www.flytierspage.com/jgordon/gordons_black_fly_larva.htm

In the late eighties I realised that, given the enormous numbers of black fly larvae which covered the rocks and streamside vegetation in the rapids on local streams, they must play a role in trout diet and I asked Dr Ferdy de Moor of the Albany Museum in Grahamstown to write an article for Piscator, journal of the Cape Piscatorial Society, which I edited at the time.

‘Blackflies, Lords of the Rapids’ appeared in the March 1989 issue of the magazine and it remains the definitive angling-related article on the species in South Africa.

His article confirms studies elsewhere in the world of the density and numbers of this species in streams.

“Simulium chutteri, a species which lives in the swiftest of flowing water currents in rapids can, at certain times of the year, be found in densities of up to 400 000 individuals or 600 gm of black fly per square metre of river bed (de Moor 1982). In terms of the number of individuals collected from stones in rapids, black fly can form 95% or more of the local animals and hence can truly be considered as ‘lords of the rapids’.”

Black fly larvae are less vulnerable to trout than Baetis nymphs because they are not so easily dislodged from the rocks on which they live. This is because they anchor themselves to the rock on a mat of woven silk. The most vulnerable stage is the emerging adult. It emerges from the pupal case in a highly visible quicksilver ball of air. Here is how de Moor describes it:

“On completion of metamorphosis the adult blackfly, now encased in the pupal skin, releases air which accumulates between the body and the pupal skin. At emergence the adult fly splits the pupal skin lengthwise between the head and thorax and emerges head first enclosed in a bubble of air. Underwater the black body of the fly encased in a silvery bubble of air rises slowly to the surface. At the surface the bubble bursts and the fly, which is completely dry, takes to the, wing. During this short period of the life cycle blackfly are extremely visible and highly vulnerable to predators. During the spring when mass emergences occur, individual flies are also larger due to development of larvae in the waters during the latter part of the winter. These large adults usually have abundant supplies of fat-body reserves and provide an excellent source of protein-rich food as is well borne out by the frantic feeding activities shown by swallows, swifts, martins, pied wagtails and fish at this time of the year.

“To summarise this information and put it into the context which would make it useful for the angling fraternity we need to look closely at the life cycle stages that are most prone to fish predation. The time of the day and seasons of the year when fish are most likely to feed on blackfly (i.e. when they are most abundant) should also be identified. Unmistakably the larvae and adults are identified as the stages most likely to be fed on by fish. Larvae would be in the drift at all times of the year, but a distinct seasonal increase could be expected in spring when water levels are slowly dropping or rising. During such water level fluctuations one would expect fish to make opportunistic use of the increased supply of drifting food. Anglers might well want to model blackfly larvae with attached silk threads moving downstream with the current. The adult stage is vulnerable to fish predation during several periods of its life. Firstly, immediately after it has emerged from the pupal shuck and floats to the surface; secondly when male mating swarms fly very close to the water surface with occasional mating couples falling into the water and lastly when the female returns to the water to oviposit. The emergence period of the adults is undoubtedly the most vulnerable stage in the life of a blackfly. It is leaving its running water habitat for which it is highly specialised and during the transition to the terrestrial aerial environment, to which the adult is also very well adapted, it goes through an unfavourable environment in the drift in a highly conspicuous fashion. The mimicking of emerging black fly adult encased in a silver bubble should make a challenging task to the angler and in my opinion and irresistible food item for the fish.”

Mean Streak marker

De Moor’s reference to the white silken threads by which black fly larvae anchor themselves to the rock is interesting because Gary LaFontaine explored a similar trait with reference to black fly larvae but in the context of caddis fly larvae which also anchor themselves to the substrate by a similar method. In his benchmark book, Caddisflies (Nick Lyons Books, 1981) he mentions becoming intrigued by the fact that brook trout anglers in Maine at the turn of the last century were catching up to a hundred fish a day by using white cotton as a tippet. The old timers that he interviewed as part of his research could not explain why this worked and it was only when he went underwater himself that he found out why.

“The Maine waters all boasted heavy populations of black fly larvae (Diptera). In the streams, clustered on rocks of the riffles, the larvae usually moved by alternating their grip from a posterior to an anterior sucker, but if they were swept away a white anchor line unfurled until the insect hung taut in the current. It then started to pull itself back upstream. The silk excretion, acting as a powerful triggering characteristic, explained the effectiveness of using white sewing-thread tippet in these streams”.

In a later book, Trout Flies – Proven Patterns (Greycliffe Publishing, 1993), he writes: “On one brook in Vermont, where the white thread almost guarantees good fishing, I put on a snorkel and pushed my face into the riffle. When my eyes adjusted to the light, I recognised the strands of white silk billowing in the current. I yanked up a rock that was squirming mass of black fly larvae.”

He then realised that some caddis larvae ( Rhyacophila, Brachycentrus and Hydropsyche) also utilised this technique and so began a long search for a means of imitating this characteristic. He found it in the white Sharpie Mean Streak marker distributed by the Sanford Corporation.

http://www.amazon.com/Sanford-Streak-Permanent-Marking-Bullet/dp/B004E2INZO

“The Mean Streak marker is the basis of the magic act. There is no need for a fisherman to even change tippets, the white colour easily wiped onto the monofilament surface. As long as he keeps a tube in his vest the fly fisherman is ready for a situation where a white anchor line might be a significant factor.”

(LaFontaine’s black fly larva pattern was hardly innovative - # 16 TMC 3761 heavy wire hook, back half of the fly olive floss, front half dark gray dubbing and black ostrich or marabou at the hook eye.)

But it is not just trout that recognise and consume black fly larvae. In a paper, ‘Habitat preferences and movement of yellowfishes in the Vaal River” we find the following reference to the diet of smallmouth yellowfish:

“The gut contents of a L. aeneus population from the Great Fish River were found to be dominated by Simulidae larvae which can easily be obtained by grazing in shallow fast-flowing habitats.”

http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?pid=S0038-23532013000400014&script=sci_arttext

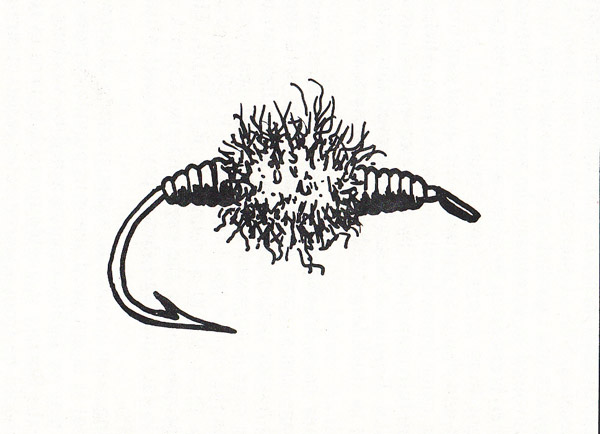

Imitating black fly larvae

A good close-up of Keith Wallington’s black fly larvae imitation for yellowfish can be found at:

http://globalflyfisher.com/fishbetter/yellowfish/pic.php?id=2525&caller=index&cl=darkframe

Keith gives his directions for this fly on page 79 of Favoured Flies and Selected Techniques of the Experts, the FOSAF book.

Hook: Scud #14 – 18

Thread: Cream

Underbody: Place lead over a quarter of the hook shank a little bit back from the eye. Tie in some clear V-Rib or fine Swannandaze at the hook bend. Wind the thread forward to the eye and colour the portion on either side of the lead with a dark brown/charcoal marker. Wind the v-rib forward to the eye and tie off. Coat the whole fly with Sally Hansen’s Megashine nail varnish. (The new UV light-cured epoxies such as Deer Creek, Loon etc, provide significant advantages such as ease of use and curing time over nail varnish)

Umpqua sell a similar pattern which imitates the Coke bottle shape and the gills.

http://flyandfin.blogspot.com/2010/10/umpquas-black-fly-larva.html

The definitive work on imitating American black fly larvae was done by Don Holbrook and if you Google his name and black fly larvae you will be taken to the relevant page of his book, Midge Magic, which he co-authored with Ed Koch. His patterns are innovative and easy to tie as they use different colours of DMC embroidery thread with the darker thread being used to form the head

Holbrook says his black fly larvae imitation has been his most successful pattern since 1976 but it seems to indicate a fundamental difference between the northern hemisphere insects and our own – they are much paler. Ours seem a uniform black, possibly because our sunlight is stronger.

If you look at the black fly larvae illustrated on Jason Wenger’s Troutnut site you will see what I mean and an illustration of Holbrook’s imitation and a description of the fly tying steps can be found on Hans Weilenmann’s site

http://www.flytierspage.com/jgordon/gordons_black_fly_larva.htm

There is however, another imitation which has a small touch of genius and which, with the addition of a 1.5mm black tungsten or glass bead, could well prove effective on our streams.

The Yong Special, developed by Andy Kim on the San Juan, Green and South Platte Rivers in the USA, developed legendary status and, like Don Holbrook’s flies, it uses Clark and Coats embroidery thread for the body. While Holbrook’s midge imitation uses two colours of thread, Kim uses only one but with a simple but significant difference – he spins the thread clockwise to create a corded, segmented appearance. Here are some links:

http://www.flyfishfood.com/2014/02/the-yong-special.html

http://cpsflyfishingandflytying.blogspot.com/2010/01/youngs-midge.html

http://www.flytierspage.com/jgordon/yong_special.htm

http://bentflyfishing.wordpress.com/articles/the-yong-special-a-deadly-midge-pattern/

You can achieve this corded appearance on slightly heavier imitations by placing the ends of two lengths of wire parallel to each other in the jaws of a rotary vise and then spinning the vise so that they twist together.

The author’s Tungsten and Wire black fly larva imitation. Note how the UV light-cured epoxy behind the bead has sagged – creating the necessary Coke bottle effect.

Competition fly fishers, justifiably in my opinion, live by the “GISS” mantra – flies should mimic the “general shape and size” of the organism being preyed upon by their quarry. Sawyer mastered this with the PTN, making no attempt to mimic the legs on the nymph because when they swam they tucked their legs against the body. Do we then need to imitate the coke bottle shape of the black fly larvae or add a little white tuft of CDC at the eye of the hook to imitate the fan-shaped food collecting organs at the head as Steve Parrott has with his pattern which is now being marketed by Umpqua? It certainly can’t do any harm and a beneficial attribute of the Deer Creek and other UV light-cured epoxies is that they remain viscous until cured by the light and this enables one to control the shape of the fly to some extent.

According to Dr de Moor, our black fly larvae reach a maximum size of 13 mm which translates into a hook size of 16 – 18 and they are predominantly black. I believe a Brassie made of black wire and a 1.5 mm black tungsten bead or a black glass bead of suitable size, coated with UV -cured epoxy, could prove a more than adequate imitation. Jeff Morgan points out that the rear third of the simuliid larva can be almost twice the thickness of the head and perhaps the answer would be to put a double layer of wire on the top third of the hook shank close to the bead.

Such a pattern would require a lot less time and effort to tie and sink faster than your average bead head PTN which is the nymph pattern of choice to imitate our Blue Wing Olive nymphs.

The pupal stage lasts from four to seven days and does not feature significantly in fish diet.

Imitating the emerger

When the adult black fly breaks free of the pupal shuck it shoots to the surface in a small silver globule of air and there have been a number of attempts to mimic these down the years.

In his article for Piscator, Dr de Moor wrote: “On completion of the metamorphosis the adult black fly, now encased in the pupal skin, releases air which accumulates between the body and the pupal skin. At emergence the adult fly splits the pupal skin lengthwise between the head and the thorax and emerges head first enclosed in a bubble of air. Underwater, the black body of the fly encased in a silvery bubble of air rises slowly to the surface. At the surface the bubble bursts and the fly, which is completely dry, takes to the wing. During this short period of the life cycle black fly are extremely visible and highly vulnerable to predators making use of underwater sight.

“The mimicking of the emerging black fly adult encased in a silver bubble should make a challenging task to the angler and in my opinion an irresistible food item for the fish.”

Others have written about this visual element. W S Roger Fogg in his book, ‘The Art of the Wet Fly’ (A&C Black, 1979) says that the emerging insect is tiny and that “… a little silvery bubble is all that can be detected.”

The little silvery bubble is however, highly visible to trout as Ralph Cutter points out in his book ‘Fish Food’ (Stackpole 2005). He writes about watching emerging black flies with his face underwater. “I saw silver bubbles corkscrewing skywards. When the bubbles hit the surface and popped, out sprang black flies.”

One of the most innovative patterns to mimic this stage of black fly life – which never caught on – was from the Danish fly tyer Preben Torp Jacobsen and it was mentioned in T Donald Overfield’s book, “Famous Flies and their Originators” (A C Black 1972)

Preben Torp Jacobsen’s emerging black fly pattern using silver wire and cow hair covered in silicone paste to attract air bubbles.

Hook: Mustad72500 size 14

Thread: Brown

Body: “Blood red cow’s hair dubbed over a base of thin copper wire. The body material should be thoroughly soaked in silicone liquid to ensure that air bubbles adhere to the body. For or five turns of 0.15 mm silver wire are made in front of and behind the body. The impregnated hair will take a lot of air down into the water and turns of silver wire in the front and the rear will help create the impression that the ‘fly’ is enveloped in a sac of air just like the natural when its pupal stage rises to the surface. The body is short, occupying the middle- third of the shank. One could tie the fly on a much smaller hook but I want the gape and the weight of bigger hook to help me bring the fly down – the same reason for the heavier silver wire.”

Also utilising silver wire is John McGill’s Hatching Reed Smut.

I came across it in Chris Sandford’s book Fly Tyer’s Flies – The Flies that catch Fish (Medlar Press 2009).

Here is the dressing:

Hook: Barbless #20

Thread: Black

Hackle: Black ostrich herl

Gas bubble: Small clear glass bead

Body: Fine Silver wire behind the glass bead

A similar pattern is featured on the Invicta Flies website but it makes a fundamental mistake in suggesting that the emerging adult black fly ascends to the meniscus trailing bubbles and then imitating this assumed characteristic with a tail of Krystalflash.

http://www.members.tripod.com/Invictaflies/id97.htm

http://www.invictaflies.us/Nymphs/Bubble%20Smut.htm

This does not happen as this YouTube clip indicate but the silvery sheen of air beneath the wings is obvious:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GY6tq9zKLpA

See also the photographs by Dwight Kuhn:

http://dkphoto.photoshelter.com/gallery-image/Blackflies-Life-Cycle/G0000_JNVn6DvRNM/I0000iMOjih5ylcs/C0000NlzGDvOk7o4

A letter in the December 1987 issue of Trout & Salmon from of Saint-Denis in France outlined a much simpler imitation: “It is merely white Antron dubbed on black tying silk and wound along the hook shank. It looks like a small black body surrounded by a clear halo.”

It occurred to me that if you used a faceted tungsten bead in silver and shrouded it with translucent dubbing, the concept Gary La Fontaine pioneered using Antron in his Sparkle Pupa, you could well create a very effective emergent black fly imitation for the month or so at the beginning of spring when substantial numbers of these insects are vulnerable to trout.

A simpler version would utilise a black hen hackle ahead of a faceted silver tungsten bead.

The author’s hypothetical emerging black fly pattern which is based on a faceted 2mm silver tungsten bead.

I first anchor the bead in the middle of the hook shank with UV-cured resin and then loosely dub black UV Ice Dub in front of it. I then comb this backwards to loosely shroud the bead and finish off with one turn of black marabou as a soft, mobile hackle.

Imitating the adult

Dr de Moor says of the adult black fly: “The adult stage of the black fly is best recognised by its humped back shape from which it derives the American name of Buffalo Gnat. They vary in size from 3 to 6 mm about the size of a match head in layman’s terminology.”

In Britain, anglers call adult black fly reed smuts and John Goddard developed an imitation which he called the Goddard Smut. He regards it as imperative when using hooks of #18 or less, to slightly bend the hook point to one side which improves the hooking ability on such small patterns.

Hook: Fine wire #18 – 22

Thread: Black

Body: Two black ostrich fibres or black wool

Hackle: Two turns of black cock hackle, short in the flue.

In the USA, Ed Koch tied a similar fly, the Herl Midge. He added a hackle fibre tail and dropped the conventional hackle at the eye of the hook. His book, Fishing the Midge (Stackpole Books) made its debut in 1972 and was subsequently updated. I read it again and again and my favourite chapter was the one on the Herl Midge. He was fishing the Young Woman’s Creek in Pennsylvania with his wife, JoAnn. He sat watching a productive pool. “Several minutes passed without incident, then at the head of the pool a trout rose. The rise was just noticeable – no more than a minute dimple in the surface. It wasn’t till then that I noticed a swarm of tiny black flies hovering over the water at the end of the riffle. A minute later another rise came at the same place. During the next quarter of an hour the same small trout rose twenty three times and, as I watched, seven more trout began feeding at the edge of the quiet water. They were taking the little black flies as they touched the surface. ‘Well, I’ll be damned’, I muttered to myself. I managed to grab a couple of flies out of the swarm. They were midges – minute two-winged water-bred flies that I later came to know well. I hurried back to tell JoAnn what I seen.”

Back at camp, he came across some black-dyed ostrich herl. “The short-fibred herl seemed just the thing to imitate the blurred wing pattern of the midges.”

He tied up a few #22 patterns with a conventional rooster hackle tail and a herl body.

He returned to the same pool in the late afternoon and the herl midge produced five trout in half an hour. Thereafter, in the next two and half hours, he brought another nine to the net – on a stretch which in the morning had produced only one fish on other patterns.

However, while searching my book shelves for more information, I came across J C Mottram’s “Fly Fishing – Some New Arts and Mysteries”. It was originally published in 1915 but my copy is a 1994 Derrydale Press reprint.

Mottram was decades ahead of the field in many respects. Half a century before Neil Patterson started work on his suspender midge using a polystyrene ball wrapped in nylon stocking material, Mottram was achieving the same objectives with cork.

One of his patterns had a body of black wool and used a tiny hackle from a starling wing – very similar to the fly which John Goddard later named after himself.

“For me, smutting fish make the most interesting fishing; is there a fishing enjoyment more delightful, more satisfying, or more satisfactory than to take a goodly two-pounder from a weedy stream with a little smut on fine gut,” he wrote.

A hundred years after he wrote this book, Mottram’s words are just as apt, just as evocative and if he were alive today he would marvel at how technology has replaced his organic “fine gut” with synthetic 8x Stroft.

Here is a further thought. 100% of all Baetis adults end up in or under the water. This is because the female crawls under the water surface to lay her eggs and the male crawls with her to create a distraction, effectively offering themselves as sacrifices to increase the chances of the female successfully laying her eggs. To breathe while underwater they carry a bubble of air between their upright wings. Neil Patterson was the first to exploit this facet of mayfly behaviour with his Sunk Spinner pattern. You can see photographs of this egg-laying behaviour on page 88 of The Trout and the Fly by Brian Clarke and John Goddard (Ernest Benn, 1980) and there is also a photograph on the cover of the outstanding DVD, Bugs of the Underworld by Ralph and Lisa Cutter

http://www.amazon.com/Bugs-of-the-Underworld-DVD/dp/B001MXZ61M

Clarke and Goddard note that these mayflies – our most common species, usually known as Blue Wing Olives – spend up to 35 minutes underwater during this egg-laying process before re-emerging and that quicksilver bubble air is a powerful visual element which trout will key on.

The sunk black fly adult

Black fly females also tend to end into the water after the rigours of egg laying. If you use a 2 mm metal or glass bead and a wire body on a #16 up- eye sedge hook such as the Grip 14723BL or the Hanak H360BL it will drift hook eye facing downwards and hook point facing upwards. In the illustrated pattern I have used a rotary vise to twist black wire into a cord for the body and then covered it with UV light-cured resin. If you then tie in a wing beneath the hook shank it will enhance that posture and the pattern’s resemblance to an adult which has been pulled beneath the surface by the tug of the current. You could use bridal organza, cling film, raffene or CDC for the wing.

A sunk adult black fly pattern using a glass or tungsten bead, a furled wire body and an organza wing.

Another alternative for the wing is ethafoam packing material as exemplified in Steve Schweitzer’s very attractive PeeMew Midge which is described on the Global Flyfisher website.

http://globalflyfisher.com/patterns/peemew/

More work needs to be done on developing suitable patterns for the first few weeks of our spring when huge numbers of small black insects become available to trout that are feeding hard after the rigours of winter floods and the rigours of spawning.

As a starting point, have a look at the adult patterns which Jeff Morgan has developed.

https://planettrout.wordpress.com/tag/jeff-morgan-fly-tier/

http://www.west-fly-fishing.com/feature-article/0204/feature_658.php

Think about this for a moment: Every one of those thousands of black fly larvae that densely carpet the rocks in the rapids of the streams near Cape Town and elsewhere is going to have to make that hazardous and highly visible journey towards the meniscus. When that happens there can be no doubt that trout will key on them. Fifty percent of them, the females, will probably end up back in the water after laying their eggs on the rocks in the stream. Baetis adults, also carrying a quicksilver-like triggering characteristic must also be a common underwater sight for fish. There must be merit in researching and tying patterns which exploit this fact.

In closing: In his book Nymph Fishing Rivers and Streams Rick Hafele makes a telling point: “The five most available insects are quite small – Pale Morning Duns are the largest and they reach only size 16 – which points out why small patterns are so often effective.”

I am indebted to the Rhodes-based guide, Fred Steynberg for his photographs of the contents pumped from a trout’s stomach and black fly larvae.

In a future article I will look at the Mountain Midge and patterns to imitate the adult.

Ed follows on about his prottype black fly nymph pattern in a postscript article at http://www.tomsutcliffe.co.za/fly-fishing/friend-s-articles/item/967-the-black-fly-challenge-%E2%80%93-a-postscript-ed-herbst-writes.html