The Neutral-Density Dragonfly Nymph

The nice thing about this pattern is that it tends to swim the right way up. So many otherwise good looking dragonfly nymph patterns swing upside down in the water. And you also have some control over this pattern’s sink rate. Because you use a wool under-body, the fly can absorb a lot of water, get heavier and sink faster. Conversely, if you squeeze water out of a wet fly it will tend to sink slower, even float for a while. So the purpose of the ND Dragon is to have a pattern that swims the right way up and that you can fish anywhere, even in shallow water over weed beds.

The triggers are the large eyes and coffin shaped body, but one of the best triggers is unlocked when you fish it with a jerky, erratic retrieve. I also like a fly that’s fairly simple to make and while the ND Dragon is not exactly that, it’s also not a solid day’s work either.

What you will need to tie this fly

You will want a 1X to 2X long, heavy wire hook, from size 6 down to size 10 for smaller, stream patterns. Use olive or brown 6/0 tying thread. Both SLF and seal’s fur dubbing are ideal for this pattern, though if you can’t get hold of either, a hare’s fur and Antron blend works well.

Golden olive and dark brown are the colours you want, but I add a touch of black and red to both olive and brown to get a muddier, more buggy looking mix. You will need a piece of four ply knitting wool (natural wool, not synthetic), around 15 cms long. Colour doesn’t matter because you are going to hide it. Finally for the eyes use red, orange or bright green Tuff chenille.

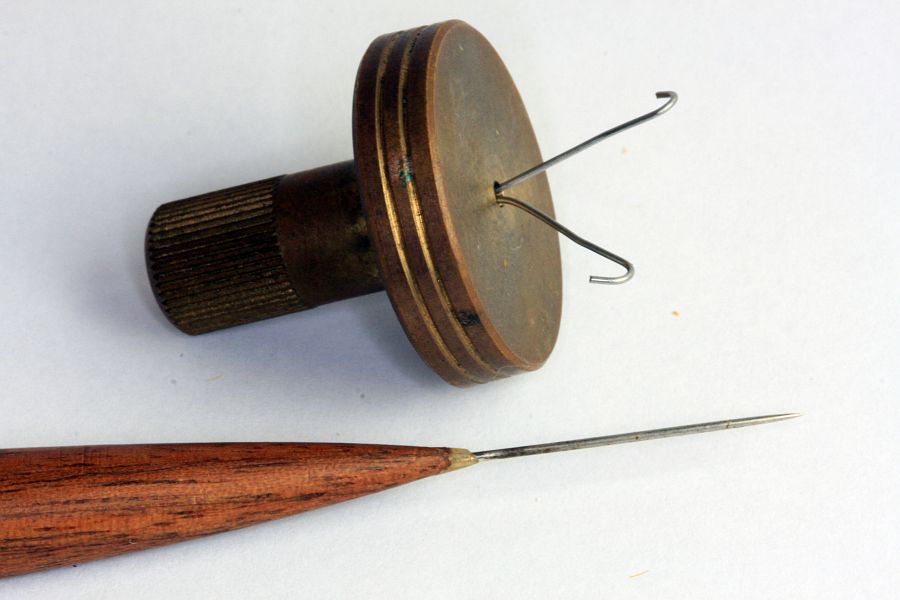

You will be spinning two dubbing loops so a dubbing loop spinner and a bodkin to pick out hair fibres are important tools.

Tying steps

Tie a section of Tuff chenille at a right angle to the hook shank about 3 mm behind the eye. I suggest you anchor it with figure of eight wraps, then form a small loop from each arm, anchor well and trim off. It is important to strengthen the chenille eyes by wrapping thread around the base, just as some tiers do with hair wing dry flies.

Dress the entire hook with silk and put in a 10 to 12 cm dubbing loop of tying thread right at the tail end of the dressed shank and leave it dangling there. You will return to it later. Unravel the wool so that you end up with a single strand. Tie in the strand of wool at the tail of the fly and take your thread to about 3 mm behind the eyes.

Start wrapping back towards the Chenille eyes. Don’t wrap too tightly. Keep adding wraps of wool until you have formed an under-body that has the typical coffin-like shape of the natural’s abdomen. Put in the last of the wool under-body wraps where you first tied in the wool. Cut off and trim any excess. What is vital with this pattern is to leave a distinct waist, or gap, between the abdomen and the head and thorax.

Now tie in a second, shorter piece of wool and using figure of 8 wraps between the eyes, form a wool under-body thorax. Don’t overdo it.

Using your fingers and working over a clean piece of white paper, mix various quantities of your seal’s fur (or other dubbing) until you get a natural looking olive brown shade.

Now return to your dubbing loop at the tail of the fly and wax both its arms. Place the dubbing between the arms of the loop having worked it in your fingers into a single, long, very thin platform of dubbing.

Now close the loop and spin it very tight.

Once done remove any obvious areas where the dubbing has clumped too densely. Again using your fingers just pull out excess material.

Begin wrapping from the tail of the fly and after each fully completed wrap, stroke the hairs backwards with the fingers of your left hand to hold them out of the way as your right hand puts in the next wrap of dubbing. Continue to do this until you have covered the entire abdomen. Usually I just make it just before the dubbing loop runs out of gas, but if I don’t, I bring the silk back to that point, tie off the first loop and add a shorter second one to get the job done.

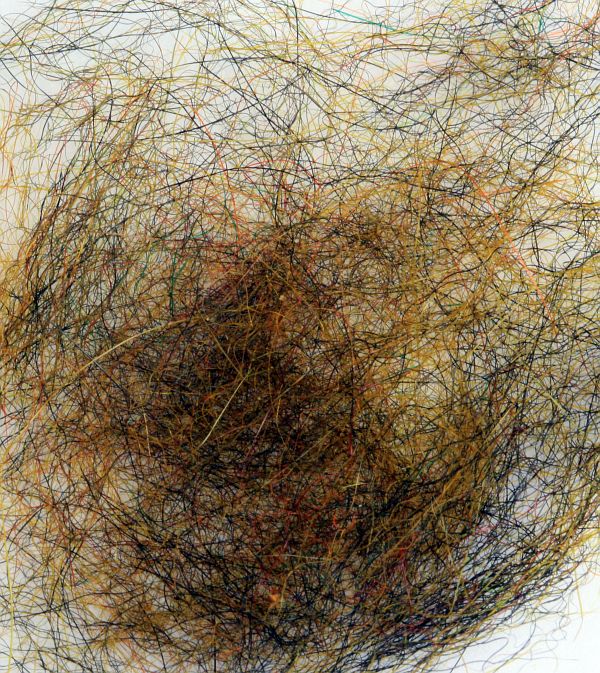

Now you need to trim the fly. Begin by teasing out as many trapped strands of hair as you can using a sharp bodkin.

Then trim the hair on the underside flat and the sides into the conical shape of the natural. It’s a sort of fly tying barbershop job this and your first couple of flies might end up more like punctured rugby balls than a dragon nymph body. With a little practice, though, the bodies get to look a lot more like the real thing.

Put the hook back in the vice, form a shorter dubbing loop in the gap between abdomen and thorax and using figure of eights around the eyes, dub over the head and thorax of the fly just as you did for the abdomen. Tie off and trim, then tease out a few straggling hairs to represent the legs.

Fishing the ND Dragon

Fetch a bowl of water from the kitchen and drop this fly into it. At first it will float, but obviously it will steadily absorb water and eventually sink.

But before that happens, submerge the fly under the water and squeeze it hard between your fingers. You will see trails of tiny bubbles popping out as you compress the air from the wool.

Now the fly is ‘heavy’ (or at least as heavy as the combined weight of the water in it, the materials and the hook) and will sink, but notice how slowly it sinks and that it stays the right way up.

ND Dragon seen from below. Note the bubbles.

The last little experiment is to take the soaked fly out of the water, squeeze it a few times to get rid of the water then put it back into the bowl. Again it will sink, but notice that it now sinks even more slowly and maintains its level position as it sinks.

So for the first time you have a little control over the sink rate of your fly – meaning we can fish it deep or shallow and right over weed beds if we want, just by adding or subtracting from the water in its body.

Let’s start by putting dragonflies and stillwaters into some sort of fly fishing perspective. Other than minnows and frogs, not much in a lake offers a trout a better meal than a dragonfly nymph.

Like damsels, dragons have easily imitated triggers – massive eyes, coffin-shaped body and a miraculous way of swimming. Tiny caudal jets blow water from the insect’s rear end and propel it forward in short, darting bursts. Of course, like damsels they also hang around structure, particularly reeds beds, but having said that, I’ve taken trout on a ND Dragon in mid-water nowhere near structure too often for it to just be blind luck. It leads me to believe that dragonfly nymphs are nomadic hunters, roaming lakes pretty freely – on a sort of aquatic invertebrate hunting safari – searching for anything edible. In that respect, they’re like any other typically carnivorous hunter/stalker. I once filled a jar of water with all kinds of lake bugs that I intended to study and photograph, but by the time I got home the only insects left were two very replete looking dragonfly nymphs that were already eyeing each other.

Dragonfly nymphs are nowhere near as vulnerable or as accessible to fish as damsels, but that doesn’t make them less sought after. I’ve seen trout turning to intercept dragonfly imitations that were metres from them. In fact, one of the most memorable moments I ever had fishing a lake was seeing a trout of well over ten pounds turn to intercept my dragon imitation in glass clear, shallow water. The fly was only a rod’s length from my tube when I saw the bow wave. That fish covered two metres in a split second and when I struck it felt like I’d hooked into a falling wall!

I fish ND Dragons on a floating line mainly, but occasionally when things are slow, I’ll use an Intermediate or a fast sinking line and a short leader. The latter provides an interesting scenario: you have a fast sinking line getting really deep, but the fly is lighter and won’t quite be following suit. That means less bottom snags and the fly, being un-weighted, has a more natural action in the water.

I have occasionally used the ND Dragon tied in smaller sizes in rivers – the Sterkspruit near the village of Rhodes in the Eastern Cape being one of them. We frequently find their shucks on stones along the river’s edge, some as long as 3 to 4 cms.

Stomach content from an Eastern Cape trout caught in a river

Shuck on a streamside stone, Western Cape

Dragon shuck found alongside a small Eastern Cape stream

It’s on lakes that this pattern really draws attention, especially around reeds, water grass and weed beds where again shucks on plant stems or reeds are common. But the retrieve needs care and attention – and concentration – to get right. It’s one of those retrieve techniques where you must keep slack out of the fly line so that you stay in contact with the fly. Add just a few quick jerks – say 5 to 10 cms – then give a second or two’s rest in between. Try to make sure you get the fly coming at different depths. In big lakes with good shallows I want the fly to fish two to three feet below the surface – unless I am leading a sighted trout or fishing to a rise.

You really want to be fishing the ND-Dragon near structure and reeds offer marvelous habitat for dragonfly nymphs.

But then I also want to be fishing a pale ND dragon to match the reed stem colours as closely as possible. This is not written in concrete but it helps in the long run.

There is often a seasonal variation to the colour of lake weeds, anything from green, to light or dark brown, almost black. I try to roughly match the colour of the pattern I am using to the colour of the weeds in the area I am fishing because I notice, like chameleons, dragon nymphs tend to take on the colours of the surrounding vegetation.

A cluster of ND-Dragonfly nymphs in a range of colours. Certainly a dark green one is missing from this mix.

Tom Sutcliffe