The Zakhåmer – Re-thinking the Klinkhåmer Special

By Ed Herbst

“The past decade has seen the rise and rise of the Klinkhåmer Special, a wonderful dry fly that seems to lure fish just about anywhere at any time. It catches trout when they are rising to naturals, but its great attribute is the way it brings fish to the surface when nothing is showing.”

Mike Weaver, columnist for Trout & Salmon and author of one of the finest books on small stream fly fishing books ever written, In Pursuit of Wild Trout (Merlin Unwin, 1991)

Klinkhåmer Special tied and photographed by Hans van Klinken

At the South African Wild Trout Association’s 2005 Fly Fishing Festival in Rhodes, one of the participants, Paul Curtis, owner of Platanna Press, suggested that I tie a Klinkhåmer Special with the same materials that are incorporated in the Zak Nymph.

The Willow Stream, Graham and Margy Frost’s farm, Balloch, in Barkly East where the Zakhåmer was first tested

Tom Sutcliffe’s Zak Nymph was named after the water bailiff who looked after some trout fishing lakes on the farm Hetherdon in the Dargle area of the Natal Drakensberg mountain range about 25 years ago.

http://www.tomsutcliffe.co.za/fly-tying/211-tying-zaks-critical-success-factors

Zak having some fun in front of the century old cottage on the farm Hetherdon, Dargle, KZN. A picture taken in the early ‘70s

The Zak Nymph

It was a halcyon age in the development of South African stillwater tactics and is beautifully described in the chapter, “The Lakes of Inhluzane”, in his book, Hunting Trout – a chapter which was chosen by Nick Lyons for his book, The Best Fishing Stories Ever Told (Skyhorse Publishing, 2010).

http://www.tomsutcliffe.co.za/fly-fishing-diary/249-hunting-trout-second-edition

The Zak Nymph’s materials are a body of stripped and unstripped peacock herl, dark dun or black hackle and tail and a rib of metallic purple DMC embroidery thread.

Rainbow taken on a Zak Nymph

After spending much of his career in the advertising field, Paul turned to publishing and one of the books he wrote, Fishing the Margins - a bibliography of South African fly fishing books from 1908 until the present – contains a foreword by me.

http://www.platannapress.co.za/margins.html

Paul Curtis fishing the prototype Zakhåmer on the Willow Stream at Balloch

http://www.ballochcottages.co.za/index.php/photo-album

For the past two years he has been living in Wales and collaborating with Paul Morgan of Coch-y-Bondhu books in the publication of angling books.

I had not seen him since our time together in Rhodes and I was delighted to hear that he had recently had exceptional success with the Zakhåmer I had tied for him during a brief holiday in South Africa. Fishing the Bushman’s River in the Natal Drakensberg mountains, he had a day to remember while his friend, who lives in the area and was using other patterns, caught nothing. “Nine large brownies came to Zakhåmer - the one in the picture at 42cms was the third largest.”

One of the brown trout caught by Paul Curtis on a Zakhåmer tied by the author

Describing the fly as “remarkable”, Paul said he wanted me to tie some more. The only problem was that while I could remember him fishing the fly on the Willow stream on Graham and Margy Frost’s farm, Balloch, in Barkly East, I could not remember what it looked like. He sent me a photograph of what was left of the fly after it had taken all those lovely brown trout. It was not much help.

The photograph he sent me was not much help!

He said it had a white wing made of snowshoe rabbit foot and an orange foam thorax, but there was very little left of the fly other than a few strands of peacock herl.

***

Hans van Klinken’s original Klinkhåmer Special was an emerging caddis imitation.

http://www.tomsutcliffe.co.za/fly-tying/284-hans-van-klinken-on-his-klinkhamer-special

In one of the best books on fly design ever written, Bob Wyatt’s Trout Hunting – The Pursuit of Happiness (Swan Hill Press, 2004) he articulates why the Klinkhåmer is so successful: “The Klinkhåmer Special, originated by Dutch tier Hans van Klinken, took European fly-fishing by surprise in the late eighties. Conventional wisdom had it that big grayling and wary, selective trout tended toward small flies and tiny nymphs. Van Klinken discovered that his strange looking fly pulled fish in almost any situation, in startlingly large sizes. The special ingredient was no mystery; it was obviously the fly's sunken abdomen. What van Klinken describes as the fly's 'iceberg effect' represents the insect at its most vulnerable, floating just beneath the surface, about to begin the process of ecdysis.

"Maybe just as importantly, the submerged abdomen enables the trout to see the fly sooner and from further off. Behavioural ecologists have demonstrated that animals will respond more vigorously to artificial stimuli than they do to natural ones. Young gulls, for example, instinctively peck at a red spot on the adult's beak to obtain food. If you present a red pencil to the chicks, they will peck much more aggressively at the pencil than at the natural beak. It is possible that the deeply sunk, over-sized abdomen, including its clearly visible hook, acts as such a supernormal stimulus. Van Klinken originally tied his fly on the deeply curved Yorkshire grub hook, but hook manufacturers have since produced shapes specifically for the Klinkhåmer. The enthusiasm shown by fish for this design prompted some good anglers to claim that the parachute-hackled Klinkhåmer Special is the best dry fly ever designed. Praise indeed, but make no mistake, the Klinker is a great fly.”

Van Klinken made much the same point in his chapter in The World’s Best Trout Flies by John Roberts (Boxtree, 1994): “This fly was much like an iceberg and gave the best results when ninety per cent underwater. The abdomen hanging below the film is an obvious target for the watching fish. The upright poly yarn wing makes the fly very visible for the angler.”

I wanted the Zakhåmer to be a general-purpose attractor/emerger that, like my Something Struggling pattern, would emphasise the vulnerability factor and incorporate materials with a lot of inherent movement.

http://www.tomsutcliffe.co.za/fly-tying/276-ed-herbsts-six-pack-of-flies

It would be based on Fred’s Klink, a fly tied and used by Rhodes-based guide, Fred Steynberg.

Fred Steyberg. Photos by Tom Sutcliffe

http://www.africanangler.com/fly_article.asp?id=816

The most salient feature of this pattern is a parachute which combines a small rooster hackle beneath and supporting a partridge hackle, a development which, in its final iteration, I believe to be South African.

Fred Steynberg’s Klinkhåmer variation which was based on the dual-feather parachute developed by Tom Sutcliffe.

As a guide, Fred often has to replace overnight the flies lost by his clients and they need to be quick and easy to tie and to produce results. He starts his Klinkhåmer by stripping the herl from the bottom of a peacock quill and this forms the body. The herl at the top of the quill forms the thorax below the dual-feather parachute hackle which surrounds a post of white packing foam.

But Fred uses this pattern in a very different way to which I use the Zakhåmer. It is not a prospecting fly, but is cast only to sighted fish. This means that it does not require the buoyancy of searching patterns which, on the sort of drifts often required when fishing small streams, might result in a casting frequency of twice a minute.

The Zakhåmer, in addition to this mixed stiff and soft hackle, thus includes an orange foam thorax which is a trigger and provides increased buoyancy, a wing made of a black and a white CDC puffs for enhanced wing movement combined with fine strands of flashabou for increased visibility and fine rubber tails for maximum movement.

The Halo Hackle Parachute

I will sketch what I believe was the chronology of what I consider to be a truly outstanding contribution to fly tying - the Halo Hackle Parachute - and which I believe can be wholly attributed to Tom Sutcliffe.

Fred Steynberg also uses Tom Sutcliffe’s Halo Hackle concept in his imitation of a Wolf Spider. Note the sparseness of the two hackles in the slant tank view (below).

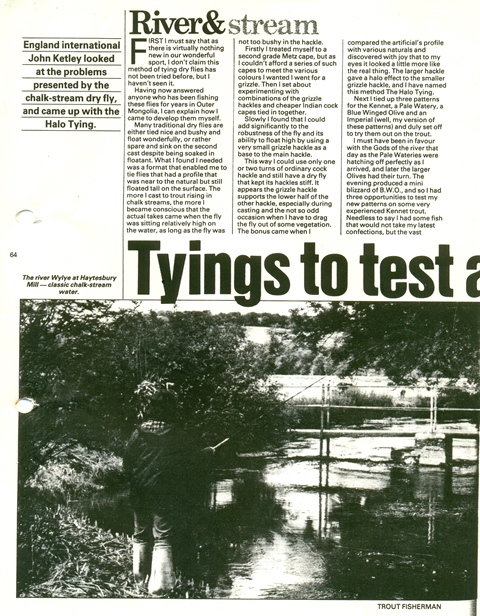

The first time I ever came across the term “Halo Hackle” was in the November 1984 issue of the British magazine, Trout Fisherman. It was in an article by John Ketley called, “Tyings to Test a Saint” and I was so intrigued I sent it to all my friends.

Ketley had scraped up the money to buy a very expensive Metz cape but, as he could only afford one, he chose a grizzly.

His other capes were more pliant Indian imports and to support the longer hackles of the Indian capes he tied a small Metz grizzly feather behind the larger feather and wound it through this feather to support it.

“I found that I could add significantly to the robustness of the fly and its ability to float high by using a very small grizzle hackle as a base to the main hackle.

“This way I could use only one or two turns of ordinary cock hackle and still have a dry fly that kept its hackles stiff. It appears the grizzle hackle

supports the lower half of the other hackle, especially during casting and the not so odd occasion when I have to drag the fly out of some vegetation.

“If you look at the profile of the Halo Patterns I have tied, despite my limited talents with hackles and hooks, you will notice how the small grizzle hackle seems to represent those minute feathery bits around the insect's head, while the longer hackles look like the legs and wings.”

To his delight, the Halo Hackles proved exceptionally successful on some demanding beats of the Test – hence the title of the article.

John Ketley’s article in the November 1984 issue of Trout Fisherman magazine. To the author’s knowledge, this was the first time that the term “Halo Hackle” had been used.

As always in fly tying, there were earlier, similar concepts. The idea of combining a small and a large feather in dry flies is attributed to Dr William Baigent of Northallertin in England who died in 1935 aged 71.

Ernest Schweibert in his book Trout (Andre Deutsch, 1979) writes: “Variant-type flies originated on the rivers of Yorkshire in 1875, where sparse wet flies had always been tied, and it is logical that dry flies with exaggeratedly long hackle fibers should evolve there. Doctor William Baigent originated the variant-style dry fly and evolved a series of twelve patterns that became known commercially as Refracta flies. Baigent believed that the shiny fibers of his long gamecock hackles created the illusion of fluttering life, as well as floating his flies easily on relatively swift currents.”

Here are two other references to Baigent’s flies: “He always tied the long hackle in grey, cream, or misty grey neutral shades and the small hackles, representing the legs of the fly, in a darker shade. The large neutral hackles, long in fibre, disturb the surface of the water on which the fly is floating and produce an alternating refraction which, he claimed, gives the appearance of wings fluttering on the water and also provides a semi-transparent look to the shorter hackles representing the legs. They produce well and are fish getters everywhere.”

Tom Sutcliffe, who applied Baigent’s theories to parachute flies

In an article, “Dr Baigent and the Long-Hackled Fly” carried in the Ozark Flyfisher’s Newsletter, Terry Finger wrote: “Dr. William Baigent … studied theories of light refraction and believed that optical patterns created by long-hackled dry flies provide a better imitation of fluttering wings than conventional flies. The long-hackled flies also floated well on swift currents and were less likely to spook trout in quiet water because they settled gently on the surface. He developed about a dozen fly patterns intended to imitate common local insects. The flies came to be known as "variants" to indicate that their proportions deviated from conventional standards. He later produced a series of flies that were marketed commercially by Hardy's as Refracta flies. These variants used dark-centered badger or furnace hackle or employed hackles of mixed length a short hackle to represent legs and a longer hackle to provide optical and floating qualities.”

http://www.ozarkflyfishers.org/media/newsletters/nl_y08/nlfeb_y08.pdf

But, from what I have been able to glean from contemporary Hardy catalogues, Baigent tied the small feather behind the big one and did not wind it through the larger hackle as Ketley described in his 1984 article.

The first South African reference to the idea came in an article - “The Halo Hackle – The Incredible Lightness of Being” - that Tom Sutcliffe wrote for the first issue of The Complete Fly Fisherman in November 1993.

“Wind the first (small) hackle up to the second and then suspend it temporarily at this point trapped in your hackle pliers. Pick up the second (spade) hackle and wind a single, full turn around the hook shank. Never be persuaded to make more than one turn, otherwise you destroy the very essence of the pattern and detract from its delicacy and movement. Tie off the spade hackle and wind the first hackle through and pass it to the eye where you can tie it off.”

Tom Sutcliffe’s sketch of the Halo Hackle principle in the CFF magazine

He gave two dressings – one with two dun rooster hackles and one with a grizzly base feather and the other, bigger feather a guinea fowl neck feather – and it is the latter pattern that I would submit is the most significant because it was the first which, to my knowledge, combined stiff hackle and soft in the Halo Hackle format – but more of this anon.

In 2000 Tom Sutcliffe became interested in Coq de Leon feathers after reading about them in Darrel Martin’s book, Fly Tying Methods (The Lyons Press, 1987). I gave him some that I had ordered through Orvis and he also bought some at my suggestion from Phil and Mary White who were then running Lathkill Tackle in England.

The obvious use for such feathers was in Variants – what the Americans call Spiders – such as Tony Biggs’ RAB. Tom told me, however, that he had also tied some halo hackle parachute dries and Klinkhåmers with them and that they had proved very successful on our streams. Two of the dries were featured in an article - “Spanish Feathers – Making better dry flies better still” - he wrote for the June 2000 issue of the South African magazine Flyfishing: “So I tied a few RABs and, depending on your level of addiction to this lovely pattern, I’d say they look mouth-watering. Some people might think that the hackle is too broad, but I’ll live with that – you could make them narrower if you used just the tip of the feather.

Two parachute dries tied with Coq de Leon feathers by Tom Sutcliffe for his June 2000 article in the South African magazine Flyfishing

“And since I’ve developed this growing conviction that parachute flies actually get more takes , and that halo-hackle parachutes get the most, I tied a few of them as well. Same result.”

http://www.tomsutcliffe.co.za/fly-tying/81-tying-the-halo-hackle-klinkhamer-emerger

Foam Thorax Parachutes

In May of that year Oliver Edwards had written an article in the British magazine, Flyfishing and Fly Tying about an ingenious method of tying parachute patterns which had been developed by the Danish guide, Morten Oland. Oland folds a piece of foam into a u-shape and cups the wing post on either side from below the hook shank. This adds buoyancy and gives the parachute hackle something to dig into. It seemed logical to me to add this feature to Tom’s Halo Hackle Klinkhåmer parachute and I wrote about this combination in November 2000 issue of Piscator, annual journal of the Cape Piscatorial Society, which I edit.

An illustration from the November 2000 Piscator showing the Oliver Edwards sketch of the Morten Oland foam thorax on parachute dry flies which the author then added to Tom Sutcliffe’s Halo Hackle Klinkhåmer

But Tom had taken the Halo Hackle parachute a step further and I only became aware of this a few years later when I saw how Fred Steynberg, one of South Africa’s most experienced guides, used a combination of a rooster and a partridge hackle as a parachute on two of his patterns, an imitation of a spider and an emerger.

At this juncture it must be said that combining a rooster hackle and a game bird feather on a dry fly has been around for more than a century.

One of the earliest such patterns had its origins, apparently, in Slovenia and was attributed to a local fly fisher, Josip Bravni?ar, who used it with great success on the Tolminka River. It was brought to the attention of a wider audience by a visiting German angler, Alexander Behm, who wrote an article about it in Die Angelsport in 1928.

The famous French fly tying company, Devaux, that invented a dry fly style in which the hackle is cupped forward, combined rooster and partridge hackles on some of these patterns.

http://www.mustad.no/action/flyofthemonth/archive/yellowpartridgedevaux.htm

Datus Proper describes what he calls a “Bent Hackle Fly in his book, What the Trout Said. (Knopf, 1982).

http://www.flyanglersonline.com/features/oldflies/part87.php

Datus Proper’s Bent Hackle fly from ‘What the Trout Said’

In Britain, patterns such as the Gingler (also called the Jingler) and the Welsh Partridge have been around for a long time but these are all, however, conventional dry fly designs or what Hans van Klinken calls “shoulder hackle” flies – not parachutes.

http://northcountryangler.blogspot.co.uk/2012/04/not-wanting-to-sound-like-broken-record.html

The Jingler, a fly developed on the Tweed River – as tied by Matthew Eastham of the northcountryangler blog

You can see Fred’s spider pattern – which imitates the local Wolf Spider (Lycosidae) which is common to riverine habitats in South Africa.

I asked Fred about this hackle configuration and he said he got the idea from Tom when he had visited Rhodes for a clinic he and Fred had held there.

The author watches Fred Steynberg, ( http://www.linecasters.co.za/) tie his Klinkhåmer variation at Fred’s home in Rhodes. Photo by Andrew Ingram

Fred does not use the Morten Oland foam wing support on his Partridge Halo Hackle emerger. I do because, while Hans van Klinken advocates up to six hackle wraps on his Klinkhåmer Special as a means of increasing buoyancy, the Morten Oland foam thorax method provides the extra buoyancy which allows a very sparse halo hackle parachute that creates the broken light spectrum and alternating refraction that Baigent and then Tom Sutcliffe specifically sought. This is facilitated and enhanced in the Zakhåmer by an extremely sparse hackle tying method which is obtained by pulling the barbules from one side of both the rooster and the partridge hackle and using only one turn of each.

“Shaving Brush Wings”

In Bob Wyatt’s Trout Hunting – The Pursuit of Happiness (Swan Hill Press, 2004) he makes a derogatory reference to the poly wings on parachute patterns in general and the Klinkhåmer in particular: “I don't like the blunt profile of those shaving brush polypropylene sighting-posts, a fly-tier's trope that, to my eye at least, spoils an otherwise good prey-image.”

I wanted more movement than the conventional “shaving brush” wing on the Klink and I also wanted it to be easier to see. For this reason I chose to make the wing with two CDC puffs - one black and one white - to create as much movement as possible, combined with a few strands of fine Flashabou dubbing that emit tiny sparkles of light and make the fly more visible.

Wing colour

In an e-mail survey I carried out for an article in the 2011 edition of Piscator the consensus of some of the best small stream fly fishers in Cape Town was that, when using synthetic wingposts on parachutes, trout were more likely to refuse brightly coloured versions such as pink and chartreuse than white. They had also found that, in the late afternoon sun, orange wingposts became less easy to see and that, in such conditions, chartreuse was the best choice. I believe the mixture of black and white CDC fibres in the Zakhåmer would thus be a safer option.

CDC Wings

In 1987 I ordered a copy of French Fishing Flies by Jean-Paul Pequegnot and then imported some dyed CDC feathers of appalling quality. While fishing the Holsloot stream near Cape Town I stopped for lunch and cast an experimental CDC fly I had tied into some shallow and slack water near the bank where I had never previously caught a fish. As I ate my sandwiches and watched the fly I was intrigued by the way in which the slightest breeze ruffled its delicate fronds and caused it to move almost imperceptibly on the water. My reverie was interrupted when the fly disappeared with a splash. Surprised, I released the fish, dried the fly as best I could and cast it back to the same spot. A few minutes later it was taken by another trout but, by then, the fly was beyond redemption and I decided that CDC flies were not practical for Cape streams.

Fast forward now to the 26th FIPS-Mouche World Fly Fishing Championship in Portugal in 2006. The South African team finds that they will be competing on heavily-fished, shallow streams which flow slowly because of the many weirs. It is clear that they would need 8x tippets and small flies which is of no concern because they had tied patterns down to #24. They quickly discovered that their hackled flies twist such tippets and that the Portuguese team are exclusively using tiny CDC dries. Because the CDC feathers collapse and compact in casting, they do not twist light tippets. What is even more of a bonus is that when the momentum of the cast dissipates, they pop open again and drift down softly like little dandelion seeds.

Because of the poor quality CDC I ordered from overseas, I lost out on a lot of fishing success and pleasure in the nineteen seasons that elapsed before the availability of good CDC and the advent of Marc Petitjean’s book and fly tying tools, saw the use of CDC flies become routine on the small streams near Cape Town. My choice of CDC wings for the Zakhåmer was predicated on those lessons.

Foam Thorax

As indicated earlier, I believe Morten Oland was the first to come up with the foam thorax which cups the hook shank and the wing from below on parachute patterns to create more buoyancy and make the parachute easier to tie and others have since followed suit.

http://www.kossiedun.com.au/Compressed%20Emergers%20&%20Duns.htm

There is another way however – starting off with the foam on top.

http://www.tomsutcliffe.co.za/fly-tying/150-agostino-roncallo-parachute-fly-method

http://www.flyforums.co.uk/fly-tying-patterns-step-step/51933-ez-klinkhamer-peter-dunne.html

http://www.flyforums.co.uk/fly-tying-patterns-step-step/16757-foam-post-klink-fpk.html

http://www.gwentanglingsociety.co.uk/flies/grayling/klinkhammer-variant.html

Whether Peter Dunne or Agostino Roncallo originated this method, I don’t know.

For the maximum buoyancy one could, of course, combine this top-of-the-hook method with the Morten Oland method of using a strip of foam to cup the hook shank and the base of the wing from beneath and, at the same time, also use Fred Steynberg’s wing of thin, translucent ethafoam. You could add even more flotation by replacing the peacock herl beneath the parachute hackle with a thin strip of black Razor Foam but that would remove what Hans van Klinken regards as a significant trigger.

With a little help from my friends – the author tying a Zakhåmer. Photo by Jeanne Welsh

When it comes to the foam thorax, nothing compares with Larva Lace dry fly foam in my experience. It is soft and thus compresses easily, light and thus buoyant and has a nice sheen. I used to get mine from Bill and Kathi Morrison of Bear Lodge Angler in the USA, but it is now available locally from Morne Bayman of the African Fly Angler.

I choose orange foam because of all the many occasions when I have had trout rise to my orange yarn strike indicator and Jeremy Lucas uses an orange post on his Oppo emerger because he says it is a trigger.

Hooks

I prefer the Varivas Terrestrial T-2000 now being brought into this country by Morne Bayman of the African Fly Angler.

The author’s favourite hooks for Klinkhåmer patterns. They are now being imported into South Africa by Morne Bayman of the African Fly Angler

Unlike most sedge-type hooks it is quite flat on top before going into the curved section and this provides a lot of room for positioning the wing and foam thorax while still leaving a substantial section for the sub-surface section of the fly.

A hook that Tom Sutcliffe finds eminently suitable is the Daiichi 1160 designed especially for Klinkhåmer patterns by Hans van Klinken himself.

The Hans van Klinken Daiichi 1160 model

If you used Razor Foam for the thorax, you could probably tie the Zakhåmer down to #18 or #20 and, in that case, I would choose the Varivas 2200BL B or the Daiichi 1160 as the hook and Uni Caenis 20/0 as the thread.

Tails

I first started using rubber tails on nymphs, soft hackles and emergers when I came across a fine, translucent material called “Bait Cotton” in tackle shops catering for bait anglers. It is used in rock and surf fishing to tie soft baits like prawns onto hooks. It was easily mottled with permanent markers and gives flies a lot of movement. To me, it made a common sense substitute for the stiff and sharp goose biots used on nymphs like the Copper John and a worthwhile addition to soft hackle flies. Then the Montana Fly Company brought out “Tentacles”, which in its small version was even finer than bait cotton and could be mottled with different colours using a permanent marker. I use tan Tentacles and mottle it first with a red and then a black marker.

http://www.montanafly.com/mfc_tyingmaterials/tentacles.html

The dangling, flexible tails and the orange foam thorax which the author believes are significant “super normal releasers” on the Zakhåmer

Body

When fishing small streams you want the body of the fly to sink as quickly as possible because you are usually fishing at short range and casting as often as twice a minute – which means your drifts are usually very short. So you want a slender body and I thus use the thinnest peacock herls available. I find these on peacock swords and I use two of them along with purple DMC thread. I counter-rib with the finest copper wire I can find. As is the case with my Something Struggling and Vertical Emerger patterns, I cover the herl body with a fine strip of clear plastic to enhance translucence and durability - an idea gleaned from John Goddard’s PVC Nymph.

Hackles

Fred Steynberg recommends that the rooster hackle have a width approximately equivalent to the hook gape and that the partridge hackle be about twice that. I cut the barbules from one side of the roster feather – say the right – and the barbules from the opposite side of the soft hackle. I then wind the rooster hackle one full turn clockwise around the foam thorax and the soft hackle one turn in the opposite direction. My rationale for this procedure - and I have no proof of its validity - is that this makes for a more aerodynamically-balanced fly.

Hackle Colour

I once read a lovely description – I don’t know where – of the colour of blue dun hackles, “Like smoke against the sun.” In the past, many have attributed magical qualities to blue dun hackles and, not surprisingly, a lot of effort was put into acquiring such feathers and people like William Baigent and Frank Elder in England and Harry Darbee and Bucky Metz in the USA laid the foundations of today’s genetically bred blue dun roosters.

Blue dun is Hans van Klinken’s preferred hackle colour for the Klinkhåmer and it is this colour which Tom Sutcliffe chose to combine with the Coq de Leon feather in the Klinkhåmer which he features on this site. It could be argued however that using a grizzly feather for the small hackle would increase the impression of movement. Similarly, barred game bird feathers such as guinea fowl, teal, mallard and wood duck might well provide a greater level of perceived movement than partridge. Using the split thread technique popularised by Marc Petitjean could provide a very useful CDC-hackled Zakhåmer.

The Zakhåmer – Ed Herbst’s answer to a challenge by Paul Curtis

Super Normal Releasers

The concept of “triggers” which cause an instinctive reaction in various animal species has been well documented by Nikolaas Tinbergen and other scientists in the field of ethology, the study of animal behaviour.

Shortly before the start of World War II, Tinbergen, a young Dutch zoologist, noticed something strange happening in a fish tank containing sticklebacks, a small local minnow. The fish tank was on a window ledge and Tinbergen noticed that at the same time each day the male sticklebacks would adopt aggressive postures. He realised that they were responding to the passing of the bright red van belonging to the Dutch postal service. Male sticklebacks have a bright red stripe and the females have swollen bellies. He built models which hugely exaggerated these features and found that the males would attack the model which had the largest element of red and that when a model of a female with an exaggeratedly swollen belly was introduced into the fish tank, they would become amorous – in each case ignoring the male and female fish present.

Tinbergen called these exaggerated features, “super-normal releasers” – in other words they triggered extremes of behaviour.

He and other scholars of animal behaviour postulate that predators seek positives rather than negatives, looking not at the object as a whole, but for special features they recognise. This explains why trout ignore the hook bend and point.

The super-normal releaser then, in a fly tying context, is shape/silhouette, size, posture, movement, material or colour, either alone or in combination that causes a trout to move further and with greater alacrity and aggression than it would for the natural organism on which it preys.

I was intrigued by the findings of two scientists who, in an attempt to prevent rainbow trout from eating steelhead eggs, dyed them in various colours and fed them to hatchery trout. The trout consistently chose the blue eggs first under variety of light conditions followed by red, black, orange, brown, yellow and green. (“Choice of Food Items by Rainbow Trout” Ginetz and Larkin)

The same study, also inspired American fly fishing author, Charles Meck, to produce his Patriot, a Royal Wulff derivative, where the only change was to substitute the peacock herl adjoining the segment of red silk in the middle of the body with blue crystalflash. Meck is very methodical, using a golf counter, to record how many fish he takes per thousand casts over a fishing season on each pattern. The Patriot out-fished his other attractor patterns two to one and, after he wrote about his new pattern in the July 1994 issue of the American magazine, Flyfisherman, others recorded similar success.

This also accords with the experiments of Tasmanian guide, Ken Orr, who experienced a significant increase in his success rate when he added a blue wire rib to his black seal’s fur nymph with a red tag. He felt this was the defining factor in making his 007 Nymph a “licence to kill”.

In this regard, the Zakhåmer, like the Zak Nymph, uses metallic purple DMC embroidery thread (code 4012).

A Zak Nymph tied by Tom Sutcliffe clearly showing the striking effect of metallic purple of the DMC thread.

The other colour that has intrigued me is red – particularly after I read New Zealand’s Best Trout Flies by Peter Scott and Peter Chan (Pheasant Tail Publishing, 2006). It contains chapters by 30 leading New Zealand fly fishers most of whom are guides, in the tackle trade or have represented their country in international competitions. Some concentrate solely on the big lakes but, of the 30, 22 had a bead head nymph in their list of six flies and several had a red hot spot on those nymphs. Stratos Cotsilinis said: “Personally I am convinced that at least in the tying of nymphs and dry flies, red adds a significant positive aspect to our success rate.” He experimented with a bead head nymph made of dubbed rabbit fur dyed black and adds: “… the true breakthrough came when a small red tag (two to three mm) was added to the tail of the fly. The success rate increased immediately.”

Kiyoshi Nakagawa chose six nymphs and four of them had a red tag and one red holographic tinsel rib.

The Zakhåmer from beneath showing that the orange foam thorax is visible through the two-feather hackle

Des Armstrong favours a bead head nymph with a red thread hotspot behind the bead. “The hot spot behind the gold bead acts as a trigger for the trout. Rainbow trout seem to be attracted to this colour combination. This is a ‘must’ fly for fishing for rainbow trout.”

That trout are susceptible to red has, however, been known to anglers for centuries. Izak Walton’s Ruddy Fly had a body of red wool. Many of Charles Cotton’s patterns were tied with red thread which meant that they had red heads. More recent patterns such as the Red Tag, a dry fly which is venerated as “cocaine for trout” in Tasmania and the Black Zulu, a traditional wet fly much favoured on Scottish lochs and other British stillwaters, are more than a century old. More recently, John Barr, inventor of the Copper John nymph has said that red is his favourite colour for flies. And the hotspot Pheasant Tail Nymph with a thorax of orange dubbing is a staple in the fly boxes of all teams competing in the FIPS-Mouche Fly Fishing World Championship.

In South Africa the colour red in flies has the same appeal. The late John Beams used a red tag on his Black Woolly Worm, the late Hugh Huntley’s Red Eye Damsel is a local stillwater staple and Tony Biggs used red thread on his RAB after reading that Negley Farson, author of the classic, Gone Fishing, believed strongly in the efficacy of this colour in flies. In the Zakhåmer, I would argue that that role is filled by the orange foam used in its thorax.

Gary LaFontaine said the attraction of red to fish is simple – it is the colour of blood. Whatever the reason, I need all the help I can get and this includes an orange trigger in the Zakhåmer in the form of its Morten Oland-inspired foam thorax.

Micro Klinks

The smallest Terrestrial 2000 hook that Varivas makes is #16 and on hooks smaller than that, such as its outstanding 2200BL B, one would need to use a thinner foam, such as Razor Foam for the thorax. Daiichi make the 1160 model down to size 22.

If you are as good at tying flies as Hans Weilenmann, then you can tie them down to #28 but I would then recommend that you use the 20/0 Uni-Caenis thread.

A #28 Klinkhåmer tied by Hans Weilenmann

Tying sequence

An invaluable aid to fly tying is the Loctite superglue which comes with a brush. South Africans were alerted to its use when Edoardo Ferrero, visited this country a few years ago when he was a member of the Italian team participating in the FIPS-Mouche world fly fishing championship. He did not bother with half hitches or a whip finis; he just dabbed a bit of superglue onto the tying thread and cut it off after a few wraps at the eye of the hook.

When tying off parachutes, Cape Town guide Tim Rolston uses this method rather than using a whip finish tool and I quote:

“I now use a “Super Glue Whip Finish” on almost all of my parachute patterns. Instead of multiple wraps around the post which tends to push the hackle upwards I simply wet a few millimeters of tying thread with cyanoacrylate glue, wrap twice around the base of the post, catching in the hackle and pull tight. Again the super glue trick was one learned from the Italian National Team at a World Championship event, although at the time they weren’t applying the principle to parachutes specifically.”

http://www.smashwords.com/extreader/read/17437/1/who-packed-your-parachute

I constantly apply tiny dabs of superglue through the tying process using the point of a dental pick to transfer drops from the brush to the fly.

Tying materials for the Zakhåmer

Thread: Gudebrod10/0, Gordon Griffiths 14/0, Uni Trico 17/0

Hook: Varivas Terrestrial 2000 #12 – 16 or Varivas 2200BL B in #18-20 or Daiichi 1160 #12 to 22

Tails: Montana Fly Co Tentacles (small) in tan and stippled with red and black permanent markers

Body: Two fine peacock herls and one strand purple DMC embroidery thread (code 4012).

Rib: Fine wire

Over-body: Clear plastic strip – Fishient Gliss ‘n Glow Clear Ice

Wing: One white and one black CDC puff combined with ultrafine flashabou strands. For a more water resistant wing use a combination of snowshoe rabbit foor furs in natural (white) and dyed black.

Foam thorax: Orange Larva Lace foam or Razor Foam on small hooks

Thorax: Peacock herl

Tying sequence

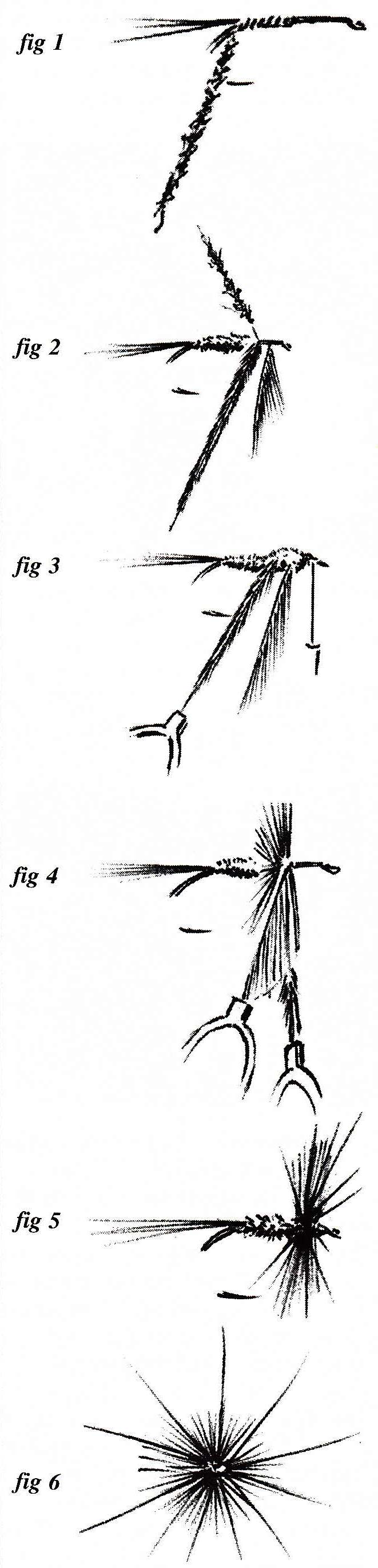

- Stipple a piece of tan Tentacle rubber strand first with red spots and then with black. Then double the strand and tie it in at the bend of the hook to form two tails.

- Tie in two strands if fine peacock herl and one strand of DMC purple embroidery thread. For ease of handling, cut the three strands to the same length and moisten them with saliva.

- Tie in a strand of fine wire for the ribbing.

- Wrap the peacock herl and purple DMC thread to a few mm back from the hook eye and tie off.

- Counter- rib with copper wire and tie off.

- Tie in the clear plastic strip (Fishient Gliss ‘n Glow Clear Ice) a few mm back from the hook eye and wind back to the start of the body at the hook bend and then back to the top of the hook shank and tie off.

- Tie in one black and one white CDC puff a few mm back from the hook eye. They must be pointing forward over the hook eye with the black puff on top. Pull the CDC puffs into a vertical position which will place the black puff closest to the hook bend and behind the white puff when seen from the angler’s position. Bind the puffs into position with a few wraps in front and behind them.

- Loop a few strands of fine mylar such as Angel Hair or Wing ‘n Flash underneath the hook shank and then bring it up on either side of the CDC puffs.

- Lock it in place with a few X wraps. This provides a subtle light-reflecting glint within the CDC fibres which makes the fly easier to track on the water.

- Place a piece of orange foam under the hook shank and pull it vertical so that it cups both sides of the wing. Lock it in place with a few X wraps of thread.

- Tie in two peacock herls at the base of the foam thorax and pointing backwards so that they are out of the way until needed.

- With the shiny side of a partridge and rooster feather facing upwards, strip the fibres from the left side of the rooster feather and the right side of the partridge feather. Tie the two feathers in so that the stripped section of the quill is against the foam with the rooster feather beneath the partridge feather.

- Wrap the peacock herl forward underneath the feathers and tie off at the eye

- Wind the rooster feather counter-clockwise one turn and tie off underneath the feather. Wind the partridge feather clockwise around the foam thorax for one turn and tie off.

The completed Zakhåmer

Watershed, Rubber Bands and Amadou

It is said that CDC floats because of the oil from the duck’s preen gland. Dyed feathers lose this oil, but the buoyancy of these feathers is also attributable to the feather structure which captures air bubbles. Watershed which is applied to a fly and allowed to dry before fishing it, is an exceptional waterproofing agent. I am glad that it is now being imported by Frontier Fly Fishing in Johannesburg and it is also available from Upstream in Cape Town. One of its great benefits is that it does not evaporate like the waterproofing agents which come in a glass container with a big lid.

If the Zakhåmer has been thoroughly slimed when catching a fish, I follow a four-step process to restore its buoyancy and to dry the CDC wing so that its fibres do not mat together to the detriment of movement:

- Thoroughly wash the fly the fly to remove the slime;

- Use the Italian rubber band method of removing moisture from the fly. A rubber band is attached to your vest and the fly is then hooked through the rubber band which is stretched. The rubber band is then twanged like a guitar string and the resultant high-speed oscillation catapults the moisture from the fly;

- Remove the residual moisture from the with amadou or paper tissues;

- Apply a desiccant powder like Loon Dust or Shimazaki Dry Shake. I am assured by CDC expert Darryl Lampert, whose flies are featured on this site that one must not blow off the excess powder.

The accessories needed to waterproof the Zakhåmer and to keep it floating

Attribution

A decade ago a British fly tyer, Ian Moutter, was sitting at a traffic light on his way home when he was struck by an innovative idea on how to hackle dry flies. The result was a book called Tying Flies the Paraloop Way. He was later to find that three American fly tyers, Bob Quigley, Ned Long and Jim Cramer, had independently come up with the same idea.

Hans van Klinken makes the same point in his article on this site: “Mike Monroe (also from USA) tied a similar fly for years before any of our patterns existed, at a time that we hardly knew what was going on at the US tying scene. He called this fly the 'Paratilt'.”

While the idea of an emerger pattern with most of the body submerged was possibly first developed by Mike Monroe, it was Hans van Klinken who developed a pattern in 1984 and Hans de Groot and Ton Lindhout who named it, that created a global brand which is to emergers what Leonard Halladay’s Adams is to dry flies and Frank Sawyer’s Pheasant Tail is to nymphs.

In attempting to establish a chronology of the Zakhåmer, I would say that the idea of mixing a small and a large hackle on a dry fly to create a broken spectrum of light has to be attributed to Dr William Baigent more than a century ago.

The name, “Halo Hackle” must probably be attributed to John Ketley and the method of supporting a softer, more willowy large hackle with a smaller stiffer one is also probably original to him.

The idea of a U-shaped piece of foam to cup the wing in a parachute pattern was probably invented by Morten Oland. I don’t know if he also applied it to Klinkhåmer-style patterns but, back in 2000 when I first saw the sketch by Oliver Edwards, it seemed a logical progression to add it to Tom Sutcliffe’s Halo Hackle Parachute Emerger.

To Tom, then, goes the credit for not only using Baigent’s combination of a small hackle and a large on a parachute, but also for creating a dual soft and stiff hackle parachute that was brought to wider public attention when Fred Steynberg used it on his emerger and arachnid patterns.

I would say that the Zakhåmer complies with all the requirements of a good small stream fly.

It is buoyant, presents softly, is easy to track in a variety of currents and light conditions and, according to Paul Curtis, is a “remarkable fly” when it comes to attracting small stream brown and rainbow trout.

http://dharmaofthedrift.blogspot.com/2011/04/6-key-features-of-small-stream-dry-fly.html

It is said that failure is an orphan but success has many parents. In the context of the Zakhåmer, the wisdom of Solomon rather than DNA tests would conclude that the person to whom most credit is due is Hans van Klinken – with a little derivative help from Morten Oland, Tom Sutcliffe, John Goddard and the Montana Fly Company. And, for spreading the word on its specific components and bringing them to the attention of a wider audience, my thanks to John Ketley, Oliver Edwards and Fred Steynberg.

Ed Herbst May 2012

Ed Herbst is one of South Africa’s leading and most respected fly fishers. He is undoubtedly our leading academic on the subject of fly fishing for trout. He is the President of the Cape Piscatorial Society and editor of its journal, 'Piscator'.

He is a master fly tyer and has a deep passion to achieve the ultimate in minimalism in small stream fly fishing tackle, flies and techniques. He has recently produced an instructional and historic two volume fly tying DVD series with Andrew Ingram titled, ‘Ed Herbst and Friends – A South African Fly Tying Journey’, available from Stream X

http://www.streamxflyfishing.co.za/index.htm