- BY ED HERBST-

In 1997, while in East London, I was introduced to a professional fly tyer, Harry Stewart, a Scot, whose Millionaire’s Taddy – a streamer made with palmered mink fur with a marabou tail - and his adult termite imitation made of spun and clipped deer hair had become legendary at Gubu Dam near Stutterheim.

Click in images to enlarge them

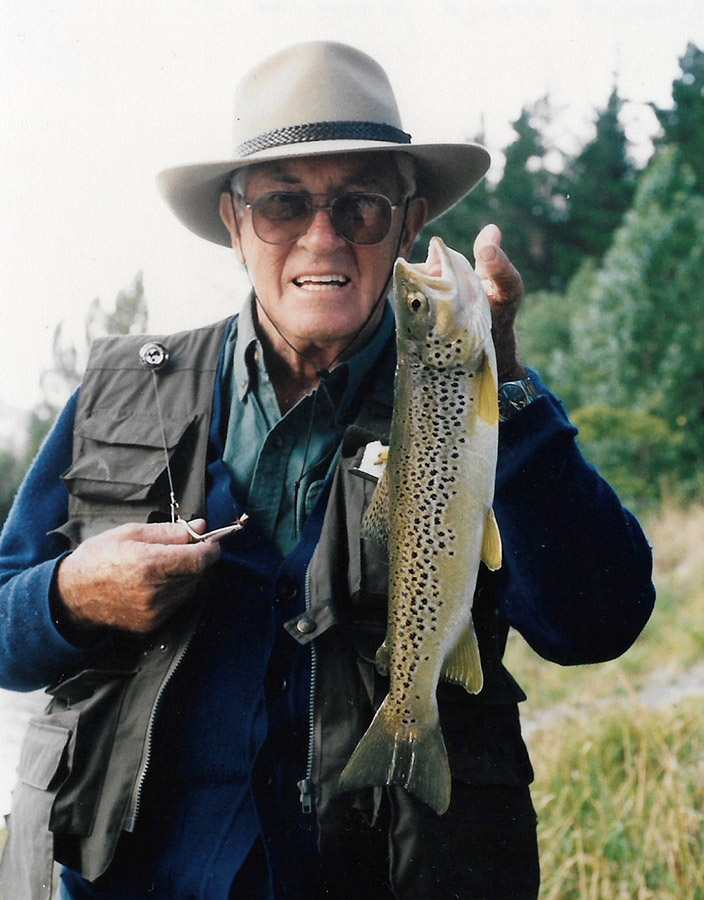

Harry Stewart – his fly tying legacy lives on in southern Africa

The Millionaire’s Taddy (above) and adult termite (below) – Harry Stewart’s signature flies which became legendary at Gubu Dam in the Eastern Cape.

I devoted a chapter to these flies in the book on indigenous patterns authored by Peter Brigg and myself.

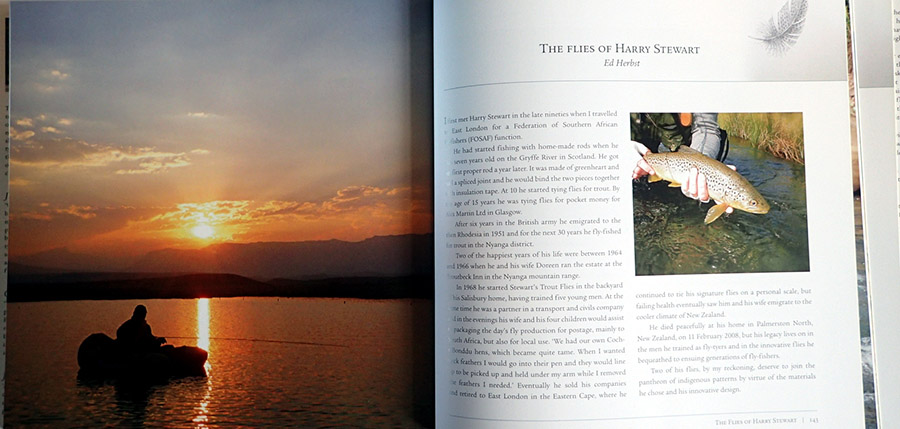

The chapter on Harry Stewart’s flies in the book by the author and and Peter Brigg

Harry and his wife moved to New Zealand where he died on 11 February 2008.

I sent his widow, Doreen, a copy of the book and she later visited me with her daughter Laura Nel while on a visit to Cape Town. Our email correspondence revealed fascinating details of how the Millionaire’s Taddy was constructed.

Doreen Stewart and her daughter Laura Nel while visiting the author

Says Doreen,

‘I got the mink from the fur coat shop in Port Elizabeth. ..bought a bag of scraps for 100 rand!!! But that source soon ran out..I then bought an old mink fur hat and cape at an auction sale which Harry laboriously cut into thin strips...on the cross of course so it would stretch when wound around the hook.

‘We got a lot of our fly tying material in one way or the other. You will know all about that!

‘Road kill came in handy...a silver fox tail in Namibia..swan neck feathers from a boat trip on the Norfolk Broads ..possum tails on the roads in New Zealand and even pheasant feathers in the Welsh hills when he stopped the car and gotout to suddenly dive in to a hedge coming out with the pheasant from which he plucked some neck feathers! He always had plastic zipper bags in the car and of course his penknife for those tails.

Harry Stewart’s mink and marabou Millionaire’s Taddy – Photo by Peter Brigg

'Harry told me that there was a secret to fishing his clipped deer hair adult termite pattern which floated like a cork. He said it was imperative not to strike at the first rise to the fly – you had to wait until the line drew away. this was because the trout would splash the termite to drown it and then return a second or so later to actually take the insect of its imitation in its mouth.'

Harry Stewart’s adult termite pattern which was extremely effective during termite hatches at Gubu Dam in the Eastern Cape – Photo Peter Brigg

Here is Harry Stewart’s story:

Harry Stewart – a fly fishing and fly tying life well spent

by Harry Stewart

I started fishing when I was about seven years old as my home was on the River Gryffe in Scotland. I knew every nook and cranny in this river, but I can’t remember being taught to fish or tie flies. When I first started tying flies I held the hook in one hand, then used gossamer tying silk in conjunction with cobbler’s wax to shade the silk different colours. It also gave me a secure holding for the horse hair which I bound on the underside of the shank of an eyeless tapered hook - size 14 or 16. I used blued hooks. I would then tie in a slip of rolled feather as a wing plus one turn of suitable hen hackle at the front of the wing — the sparser the better. So, that was the fly — simple and deadly. I was about 10 years old when I started tying flies for trout. I was 14 or 15 when I progressed to sea trout and salmon flies. I used to sell these to a firm called Alex Martin Ltd in Glasgow for pocket money. They supplied the materials - I still had no vice.

As a child, I used to sell to a Mr McFarlane small trout for his pond, at 6p each! To catch these fish I would lie on the bank, put my hand gently in the stream, under a stone and would tickle the side of the fish and gradually bring it out. I demonstrated this method years later at the Inyanga hatchery in Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) with large fish. We called it “guddling” or “tickling the trout” and when I was about six years old, my friend Martin McFee caught a three pound trout this way. He took it home and paraded it about for everyone to see. His mother covered it in fat and kept it in the “meat safe” (before fridges were invented) for many days!

I was eight years old when I got my first fishing rod. From then on, I made my own. My favourite rod for the River Gryffe was an 8ft spliced greenheart — which meant there was no ferrule. It was bound at the joint with insulating tape. My favourite rod for the Clyde river was a little heavier — an 8'6“ greenheart. I also had a 9‘6“ ash and lancewood — ash butt and lancewood top. The greenheart came from the old piers (docks) on the river Clyde at Greenock. My uncle had brought me the log (part of a support for the old pier). I had to split it down and grain the wood so that I had a good strong rod. Cross grain was no good. The lancewood came from the shafts on a cart — the centre boom to which the horses were hitched. The ash was purchased at a joiner’s shop in the village. Both these woods were very light. Again, the ash had to be split with an axe. The rods were never varnished, only the bindings on the line guides. The rod was polished with linseed oil until it achieved a varnished look. The butt was not cork. It was formed in the same piece of wood as the rod, painstakingly scraped into shape with a broken bottle. A long process!

Inyanga

After WW2, I emigrated to Rhodesia in 1951, having served six years in the Army. I very soon found Inyanga — and for the next 30 years fished every trout stream and dam in the area. It was here, at Troutbeck, that I experienced (as a raw Scotsman!) my first encounter with fishing snobbery, when a Mr Bing commented that he couldn‘t understand how anyone could fish with such a pole! I soon out-fished him and got my limit! Incidentally, he was a dry fly purist and would not fish wet fly!

The Troutbeck Inn had just been opened (1952). In 1964 we moved to Inyanga. The two years spent at Troutbeck Inn were very satisfying. I had suffered a perforated ulcer due to overwork and was recovering when I spotted an ad for an Estate Manager at Troutbeck Inn. The manager had to have a wife who could run a farm! We had spent many holidays at the hotel - we also had a cottage at Connemara (above Troutbeck; 7000ft altitude).

My ability as a maintenance man, keen fisherman and my “farm capable” wife got me the job! In truth, although I had been brought up on a farm, my wife was a real “townie”. I was offered the job and accepted! We closed up our business, sent letters to all our customers and headed for the mountains! We started just before the Easter holidays and had, in fact, spent the previous Christmas holidays there. Our family, at the time, consisted of four children - the two elder daughters were sent to junior boarding school in Marandellas, our son had correspondence school lessons taught by his mother and the baby was at home.

The outgoing manager and his wife gave us a day’s instruction and then we were on our own! The job entailed maintaining a nine-hole golf course, a bowling green, stocking trout, hatching trout, running golf tournaments, fishing competitions, forestry and the farm and garden as well as hotel maintenance, lighting plant and lots more. On the days that I required caddies for a competition, my wife would have to milk the cows herself. She took to farm life like a duck to water. It was an ideal situation — encompassing my favourite pastime as well as an outdoor life.

We improved the fishing by liming the dam. The long dam weed disappeared, leaving a carpet of weed on the bottom. The pair of swans were sold to Marandellas — they were originally put on the dam to clear the weed and were now redundant.

Transported by train

Most of our ova came from Fred Birch at the Pirie Hatchery in the distant Eastern Cape. They were transported by train to Rusape, then by lorry to the hotel - another 100 miles. We had huge successes with the ova. The 1965 season was greatly improved — the 1966 was even better. I had the pleasure of winter fishing too, when I would catch the trout, milk the male on to the ova from the females, then all the fish were returned to the dam. I had a good success rate too! Our children thrived and we were very happy.

After two years, we decided to return to Salisbury. The hotel had changed hands. We had a quick trip overseas and bought a stock of feathers, silks, hooks, etc. to start a fly tying business. At the same time, I went into partnership with my father-in-law and started up a transport and civils company. At the time of its closure 18 years later, we employed 200 people.

In 1966 I obtained government protection against imports and started a small fly tying factory in my backyard! I trained five young men, all from Inyanga. They seemed to be the best craftsmen. They were soon producing very good flies. Incidentally these young men are now married and are classed amongst the finest fly tiers in the world.

This business was strictly a side-line, and after a day‘s work in my transport and civil engineering contracting business, I would come home to check every single fly tied that day. They had to tie a minimum of four dozen each a day as we had many orders to fill, in South Africa as well as Rhodesia. My wife and four children would sit around me while I checked the flies and they did the packing. We had our own “Coch-y-bondhu” hens which became quite tame. When I wanted neck feathers I would go into their pen and they would line up to be picked up under my arm while I gently removed the feathers I needed!

Eventually we sold Stewart’s Trout Flies, as my other business was getting too big.

Kariba tigerfish

We also fished at Kariba, and prior to the Kariba dam being built, fished at Chirundu. My interest in fly fishing soon led me to develop flies for tiger fish, the best known being the “Gillieminkie”. This fly was developed before Kapenta were introduced into the Kariba Dam. The original fly was a simple tie - silvered hook 3/0 long shank with two pairs of badger cock hackles, back to back. Sometimes a large split shot was crimped just behind the eye, to make the fly go deeper. We fished mainly in Sanyati Gorge at daybreak and just before sunset. We would first “chum” with chopped up gillieminkies or small bream, whichever was easiest to obtain. (We took our gillieminkies from the dam at Henry Chapman golf course, Salisbury, transporting them to Kariba!) The “Gillieminkie” fly produced great sport although many fish were lost, as well as tackle in the submerged trees. When kapenta became established in Kariba, I changed the dressing of the Gillieminkie - using the same hook, but substituting the badger hackle for light grey dyed saddle hackles, and a silver strip down each side of the wing. Dried kapenta were purchased cheaply and a handful thrown in the water would usually attract the tiger fish. My largest fish caught on that fly was 11 lbs. It gave a great fight. This was in 1960.

While I was at Inyanga I developed the “Troutbeck Beatle” named after a Liverpool pop group, who were making their name at the time and who sported those mop-like hairstyles. This fly was my most successful trout fly — a dry. I tied it to represent a large black/brown beetle which emerged from holes in the bank under the pine trees at Troutbeck dam. When this insect was in flight it made a loud whirring sound and would then plop on to the water. Almost immediately there would be a splash as the trout drowned the beetle. I watched this procedure until it was dark. l took the beetle home with the intention of trying to tie an imitation. It took quite a few attempts before I was satisfied with the density of the fly — density enough to represent the solid body. The following evening as the beetles were again emerging, and the fish starting to rise, I put my “Beatle” on and cast it out. Within seconds a fish rose to it. I struck and missed! Eventually I discovered that by waiting about five seconds before striking, I connected every time. What sport! Those fish caught on the Troutbeck Beatle were all big fish — and all went to hotel guests.

Ill health forced me to get to sea level, where I made a good recovery and have enjoyed East London ever since!

Troutbeck Beatle

Tail: Forked slips of crow wing to represent the top of the beetle's wing tied short.

Body: Black and natural red cock hackles - approximately 8-l0 hackles on No 6 hook. Start with black and red and wind the two hackles simultaneously keeping them as dense as possible, tie in more hackles winding on until you reach the eye. Whip finish — and varnish whip. The fly can be as small as a size 16.

There is a story to this fly! A couple of hotel guests — Jack and June Dobson from Lusaka — had called at my cottage and asked for flies. My wife picked up a few of my “reject” Troutbeck Beatles and gave them to the couple. Now these people had never fished before, but had had casting lessons from me the previous evening. They had hired hotel rods. I had gone to fish the Gaerezi River, and when I returned to the hotel that evening, the bar was buzzing withthe news that the Dobsons had caught six large trout in the space of a couple of hours. They had recorded the fly used as “Harry's Reject”. When the Dobsons caught their fish all they did was cast out, and let the fly sink, and reel in - thus fishing “wet”. Their rejects were size 6 and had an additional green fluorescent chenille on the body to give bulk. The hackle was sparser. The reason I rejected them was that the green was peeping through and that wasn't what I wanted. So there we had a superb dry fly, the Troutbeck Beatle, and a “reject” which was very effective when fished wet. This fly continued to take six fish (the limit) every evening — large fish.

Flying ant

Another popular fly, both in Zimbabwe and here in South Africa, is the Flying Ant, wet or dry. I made this fly to represent small flying termites. I had been fishing the evening rise from a boat at Troutbeck when there was a sudden emergence of flying ants from the direction of the dam wall. I put on a fair imitation of the flying ant — to no avail. I then noticed that the fish were taking a much smaller ant - brown/red in colour. I changed my fly to a Greenwell's parachute and within a short time I had my limit. My original flying ant was a size 10 hook. Flying Ant Body: Kapok with brown rib — then 2 cock hackles as wings, grey/brown, tied flat on top to protrude another hook length behind. I then tied a Rhode Island red hackle in front of the wings. One of my acquaintances, a very accomplished angler, would only fish the flying ant at Connemara (dam above Troutbeck). She once told me that it was just as good without the wings!

The other flying ant was made on a No 12 hook with spun deer hair body trimmed to shape, two body feathers from the Rhodesian Partridge — light coloured and trimmed to the wing shape of a termite, then tied flat over the back, and a red cock hackle in front. This was a good floating fly. It was good to look at — very realistic, but to be honest I think it caught more fishermen than it did trout in Zimbabwe. It could be mistaken for the real flying ant.

While living in East London, I fished it at Gubu Dam near Stutterheim during a flying termite hatch when they were lying thick on the water and had been wind-blown into lanes along the banks — about l5-20 feet out. The trout were in a feeding frenzy. When I put this termite imitation on, I had immediate success. Most of the fish caught were large, taking a lot of line and jumping a number of times. They seemed to fight much better than when taken on wet fly! Other flies I have developed are numerous — the most successful being the Millionaire’s Taddy. I gave this fly to my grandson, Keith Rose-Innes, when he was l4 years old. He won the Gubu Fishing Competition - both senior and junior sections! That was five years ago and the orders for the Millionaire’s Taddy increase by the day!

Today, Keith is one of the world’s top salt water fishing guides operating out of Alphonse Island in the Seychelles – so the legacy of Harry Stewart lives on.