THE HOT SPOT

By

Ian Cox

One of the many threads that bind all fly fishers is our shared faith in a hot fly which we can turn to when the fishing is not. It is true that we do not all place our faith in the same fly even when fishing the same water together. We are after all a broad and tolerant church. It has to be said that we are also a fickle one. Just as all of us have a favourite fly, so is it that the fly of our affections changes from time to time. But I think it fair to say the fact of the favourite fly is one of the truths that give our community coherence and identity.

My first favourite fly was a Walkers yellow nymph which aged 8, I dragged to great effect against the current whenever I could prise the family fly rod (a 9ft 3 piece Hardy Jet lined with silk on a Marquis reel) from my father’s grasp. I did not get to do this very often. You see Papa liked to fish too. He also professed to be a purist albeit of the highland school. A Walkers Killer and its relatives were all uncomfortably close to a lure in those days, best left to bass fisherman trying to better themselves. Drifting a line from above the rapids was just as unacceptable, or so I was told. Me, I think it was more about who got to fish.

Click to enlarge images

The Walker's Yellow Nymph

In time my casting improved. The number of fly rods in our family grew to two. I trawled less and drifted more and I learned the knack of divesting my mother of her rod (a sweet Abu which I still miss). With these burgeoning skills and eventually a rod of my own (the cheapest Daiwa Kings could supply), came a more sophisticated favourite fly. So it was that I discovered the Invicta red tail. This served me well all through my schooldays and into university. This is not to say that I did not stray from time to time. I remember a year in high school when the Bloody Butcher was my fly of choice. As I grew older and less susceptible to parental prejudices the Walkers Killer became increasingly a favourite but mainly on still water.

The Invicta Red Tail

University opened the door to adventure sports and these inevitably detracted from what had been a consuming passion, (too consuming my teachers told me). Marriage and children followed. It was only when the convergence of advancing years and my other adventure sports led to broken bones and increasingly regular spells in hospital that I returned to my first love of fly fishing.

By then everything had changed. Fibreglass had given way to carbon fibre. The Hardy catalogue was no longer the font of all knowledge and my old favourites were now relics consigned to the dustbin of history.

I enthusiastically embraced this new world. It wasn’t long before I owned more fly rods than my father ever did. No child of mine would ever have to implore his or her parent for time with a fly rod. It is one of life’s cruel ironies that no child of mine has ever wanted to.

New ways require a new favourite fly. The Invicta Red Tail is still my first love but like all first loves, it is one that no longer meets the moment. At first I kept a couple in my fly box as a reminder of happy days, but even that did not last. I needed a new favourite fly.

I do not know if it is advancing years but I am not as fickle as I once was. It’s taken a lot longer for me to fix my affection than it once did. I have run the full gamut in the six or so years since I took up fly fishing again in earnest. I’ve flirted with dry flies of various descriptions, frolicked enthusiastically with the Zak, dangled after emergers, toyed with the CDC creations of Switzerland and France, eyed Czech nymphs and even looked east to Japan. None have fixed themselves as my favourite go to fly, that is none other than the orange hot spot variation of Frank Sawyer’s Pheasant Tail Nymph or as it is increasingly becoming known locally, the Orange Hot Spot or simply the Hotspot.

I was introduced to this fly by a couple of years ago by Howick fly fisherman Anton Smith. A lot of water had been let out of Midmar Dam with the result that the Cascades were still exposed when the Yellowfish began to run up the Umgeni to spawn. The fishing was awesome, especially after Anton suggested that I fish a twin nymph rig, with the Hotspot being the default fly. It worked just as well at Sterkfontein and when fishing for scalies on the Umkomaas. It wasn’t long before I tried it on trout, first on rivers and later dams, both with similar success. And thus, like Scheherazade and her 1000 tales, crept the Hotspot into my affections.

The Upper Bushman's

This has been no coup de fondre. Indeed I only realised on a recent trip to the upper Bushmans (Giants Castle) that it is my favourite fly. It was another typical Giants trip. The river was perfect and the fishing perfectly awful. Nothing worked, except of course the Hotspot. It was then I realised how often this was the case. My fly box confirmed this for there, demure, forgettable even, but outnumbering every other fly in my box, was a line of well used Hotspots.

Affection brings with it a desire to know more. So where did the Hotspot come from?

Frank Sawyer's PTN

Well the first part is easy. Frank Sawyer is famous as the river keeper of the beat on the Avon owned by what was then the Officers Fishing Association, as well as an author, teacher, naturalist, conservationist and the inventor of the Pheasant Tail Nymph or PTN as it is known locally. It is a famous fly. It is one of a handful of flies that has its own page in Wikipedia.

From here on it gets more difficult.

Skues variation of the Pheasant Tail

In 1965 Frank Sawyer attributed the genesis of his PTN to an earlier pattern of his, the Pheasant Tail Red Spinner. This in turn derived from two ancient Devonshire patterns, the Red Spinner and the Pheasant Tail. Both are dry fly patterns. Sawyer said that he found that once his Pheasant Tail Red Spinner had lost its feathers it fished well as a nymph.

Frank Sawyer was introduced to nymph fishing by his boss, Brigadier Carey, who was also a friend of George Skues and a supporter of his nymph-style fishing and flies. Interestingly George Skues also developed a variation of the Pheasant Tail. It was also spider pattern which was tied with hot orange silk.

Frank Sawyer and George Skues met in 1945 when Sawyer was 39 and Skues 87. Though George Skues had only 4 years to live they became friends. George Skues introduced Frank Sawyer to his publisher A C & Black who published Sawyers first book, The Keeper of the Stream. He also introduced him to the magazine market.

George Skues’ nymphs, and perhaps even his variation of the Pheasant Tail, must have had a significant impact on the development of the PTN. The similarities between George Skues’ nymphs and the PTN are inescapable. Though Frank Sawyer disagreed with George Skues that an emerging nymph should be fished motionless, he was nonetheless a close student of his writings. He dealt extensively with George Skues' theories in Keeper of The Stream. He wrote that Skues techniques would not work when nymphs were swimming deep, but gave no indication of what fly would work, other than the fly must enter the water cleanly and sink slowly.

That came much later with the publication in 1958 of Nymphs and the Trout. He explained the delay in 1965. He said that it took years before what we know as his PTN developed into a truly deadly fly.

So why the lack of any attribution? I think that is easily explained. When asked for the origin of the fly he said it was the Pheasant Tail Red Spinner, but its development is an entirely different matter. It is also possible that he was also concerned about upsetting the dry fly movement. It is true that Halford was long dead, but the dry fly movement was not. After all, his beat changed its name to the Services Dry Fly Fishing Association in 1974. Skues, an independently wealthy lawyer could afford to ruffle feathers. I suspect that Sawyer, albeit celebrated, could not.

Until someone persuades me otherwise, I remain convinced that the PTN is a Skues nymph out of a Derbyshire spinner bred by Frank Sawyer.

But what of the Hotspot?

Al Troth's PTN

The PTN is not without its variations. Tom Sutcliffe has written of Al Troth’s American version. This fly, which was tied with thread rather than copper wire and sported a peacock herl waistcoat (thorax), was developed in the 1960’s. It is now tied with a bead head and has become just as famous as the original. Indeed the South African version of the PTN has more in common with this fly than Frank Sawyer’s original.

Arthur Cove

Another famous variant is still water fly fishing legend Arthur Cove’s buzzer version of the PTN. He developed this in the late 1960’s or early 1970’s as a still water fly. It met with instant success. In 1975 Brian Clark wrote of it in The Pursuit of Stillwater Trout as perhaps the most successful of all deep fishing nymphs. Now Arthur Cove, who died in 2009, was also famous as a fly designer of rare ability. His inventions include the Red Diddy, a fly that is so deadly that he stopped using it. There is mention on one of the fly fishing forums of him describing such a orange hotspot version of his Cove PTN fly in the mid 1980’s, though no mention in his book which was published in 1986. The book illustrates green, grey and black variations but no orange one.

The standard Arthur Cove PTN

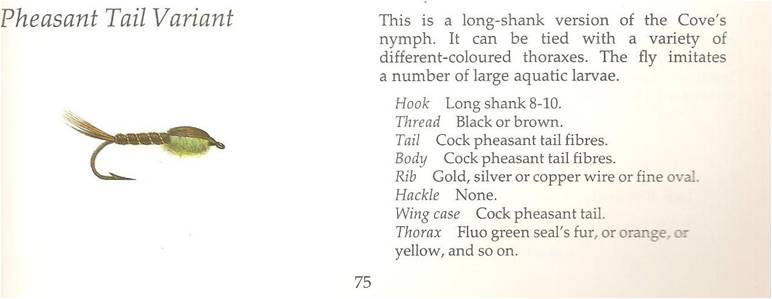

Taff Price’s Fly Patterns, An Internationl Guide, describes a variation of Arthur’s Cove’s PTN. He calls it the Peasant Tail Variant. It is described as a long shanked version of Cove’s PTN (or in other words, Al Troth’s version) but with a green or orange thorax. This is what we know as the Orange Hotspot. Unfortunately he does not say who designed it.

There is a mention in one of the UK forums of Ken Fox developing a hotspot version of the PTN in the 1980’s. I purchased a copy of his book from the ever productive Coch-y-Bundu, but again no mention of any fly that could conceivably be likened to an Orange Hotspot.

This is not to say orange nymphs were unheard of. Cove himself speaks highly of the Orange Seal Fur Nymph as a go to fly in the late afternoons or when the fishing was difficult. Its just that none of them remotely resembled the Orange Hot Spot.

The American’s are uncharicteristically silent on the subject.

I did launch the question of the origins of the hotspot into the web in the hope that this might produce a result. The question piqued the interest of the editor of Fly Fishing and Fly Tying and even made it into the June 2012 edition. I have had lots of hits but no answers. Ed Herbst and Korrie Broos pinged their contacts. The French replied saying that it was their invention, but I have found nothing to confirm this. The idea of a hotspot itself is generally regarded as an English innovation. Indeed the use of hot orange thread in the tying of the Skues variation of the pheasant tail is in essence a hotspot. Like others I had a heart stopping moment when I read Jean Paul Pequegnot’s French Fishing Flies. He writes that Jean Lysik’s Nymphe Jeannot was developed 1873, which would turn the history of nymph fishing on its head. As Ed Herbst pointed out, it is a typo. Jean Lysik was around in the 1970’s not one hundred years earlier.

The earliest South African reference I have been able to find of the Hotspot is Horst Filter’s 2000 publication, Fly Fishing for Warm Water Species in Southern Africa, which mentions Maretjie Davies using a fly very similar to the Hotspot on Sterkfontein Dam. There is also a mention of it in a 2003 article in Getaway Magazine. Dean Impson describes the fly in volume 3 of Favoured Flies. This was published in 2007. Both his version and Maretjie Davies’ sport a throat hackle or beard which brings them more in line with the Ken Fox’s super nymphs. This version of the Hotspot seems to have fallen out of favour. The version used today is identical to the Pheasant Tail Variation described by Taff Price in 1986.

So the Hotspot is not South African fly. Though its exact genesis is unclear, it is most likely an English Midlands still water creation of the late 1970’s or early 1980’s. This should not surprise anyone. After all so much that is good in fly fishing comes from this region.

There does, however, seem to be a story to tell regarding its use in this country and it’s metamorphosis from bearded version favoured by Davies and Impson to the beardless wonder used today. I wonder if our yellowfish specialists can tell us more.

___________________________